There are quite a few different notations you can use to write down...

**Chess Informant** was founded in 1966 in Belgrade, Yugoslavia (no...

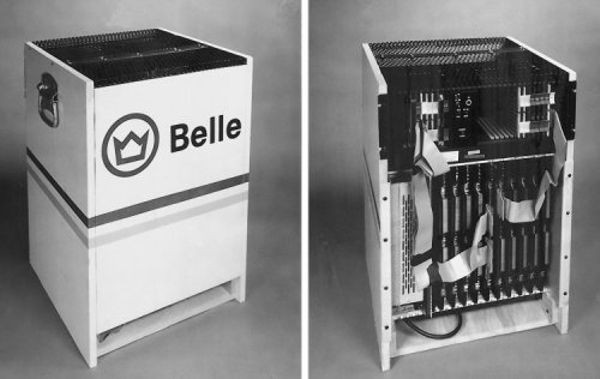

### Belle

Belle was a chess computer developed by Ken Thompson and...

**Opening books** are databases of chess openings. In Computer Ches...

#### Chess Notations for computers

Fortunately nowadays computer l...

#### Skew angle

Skew angles usually result from placing an origina...

#### em unit

The *em* is a scalable unit that is equal to the curr...

Could somebody provide a visual to help me better understand the st...

+ **O-O** Castles Kingside

+ **O-O-O** Castles Queenside

*Cas...

552

IEEE

TRANSACTIONS ON

PATTERN

ANALYSIS AND MACHINE INTELLIGENCE.

VOL.

12.

NO. 6.

JUNE

1990

Reading

Chess

Absrracr-In an application of semantic analysis to images of ex-

tended passages of text, several volumes of a chess encyclopedia have

been read with high accuracy. Although carefully proofread, the hooks

were poorly printed and posed a severe challenge to conventional page

layout analysis and character-recognition methods. An experimental

page reader system carried out strictly top-down layout analysis for

identification of columns, lines, words, and characters. This proceeded

rapidly and reliably thanks to a recently-developed skew-estimation

technique. Resegmentation of broken, touching, and dirty characters

was handled in an efficient and integrated manner by a heuristic search

operating on isolated words. By analyzing the syntax of game descrip-

tions and applying the rules of chess, the error rate was reduced by a

factor of

30

from what was achievable through shape analysis alone.

Of the games with no typographical errors, 98% have been assigned a

legal interpretation, for an effective success rate of 99.995% on ap-

proximately one million characters (2850 games, 945 pages). We dis-

cuss several computer vision systems-integration issues suggested by

this experience.

Index

Terms-Character recognition, chess, document image anal-

ysis, layout analysis, semantics.

I.

INTRODUCTION

E present an engineering case study of a complete

computer vision system exhibiting unusually high

competency in a complex application, in part through the

use of computable semantics. The system is a page reader

and the application is the extraction of chess games from

the

Chess

Informant

[5], a series of volumes describing

games of theoretical interest.

The books are poorly printed, and pose a severe chal-

lenge to conventional layout analysis and character rec-

ognition methods. Novel features

of

our experimental

page reader include a strictly top-down layout analysis ap-

proach that works rapidly and reliably, largely owing to

a recently-developed technique for estimating the align-

ment angle of blocks of text. Preliminary classification is

performed before attempting to locate baselines or parti-

tion lines into words. Broken, touching, and dirty char-

acters are handled in an integrated manner by a shape-

guided heuristic operating on isolated words.

The games are extracted using a combination of layout

and syntactic rules. Each game is segmented into moves

(50

on average), and commentary is recognized and

stripped

off.

Each move consists of a move number and

two ply (half-moves), and each ply is described in three

Manuscript received May

23,

1988; revised October

12,

1989. Rec-

The authors are with

AT&T

Bell Laboratories,

600

Mountain Avenue,

IEEE

Log

Number 9034827.

ommended

for

acceptance by

C.

Y.

Suen.

Murray Hill, NJ 07974.

108.’

(R

76/a)

A

62

Luzem (01) 1982

1.

d4

Q€6 2. c4 e6 3. 433 c5

4.

d5

e&

5.

cd5 d6 6. Qc3 g6 7. g3 pg7 8. Ag2

0-0

9.

0-0 Qa6!?

10.

h3

[lo.

e4 &g4=]

Qc7

[RR

10.

..

Ee8!?

11.

4.f4 Qc7 12.

a4

Qe4

13.

Rcl

b5!

14. Bel Rb8

15.

ad2

g5!

16. Qde4 g€4 17. ab5

f5

18. Qd2 fg3

19.

fg3

@g5

20. Qfl

Qb5F

Csom

-

Sub%

Biile Herculane 1982; 11. Qd2!?]

11.

e4

Fig.

I.

A

sample

of

text

from

the

Clless

Infurinant

(shown

1.55

X

actual

size). This is a game’s header and opening moves, including two par-

enthetical comments in move number

IO.

KORTCHNOI

-

TRlXGOV

characters on average (see Fig. 1). By applying knowl-

edge of the rules of chess (the “semantics”), each move

is checked for legality directly in the context built up by

prior moves and indirectly through the consistency of later

moves. If the interpretations of moves suggested by shape

analysis are inadequate, alternatives are generated, again

by invoking the rules of chess. Even though this semantic

analysis is fully-backtracking, intolerable runtimes are

prevented by the high quality of the shape recognition

overall and a roughly uniform distribution of serious mis-

takes.

Of the first 142 games, two were flawed by typograph-

ical errors (editorial or typesetting mistakes), and the se-

mantic analysis failed, for assorted reasons, on three

more. The resulting

98%

of games correct

implies that

99.99% of the moves, and 99.995% of the characters,

were interpreted correctly. Without semantic analysis,

only

40%

of the games would have had a legal interpre-

tation, even though the character recognition rate due to

shape analysis alone is reasonably high (99.5

%).

Prior approaches to the detection and correction of er-

rors in text images have operated on

isolated words

from

natural languages, typically by means of dictionary look-

ups (e.g.,

[2]

[l

I]

1131) and character n-gram frequency

analysis (e.g., 1141

[I61

[7]). The lack of effective and

efficient algorithms for the analysis

of

natural language

has long frustrated the natural desire to extend this to sen-

tences. The comparative tractability of the semantics

of

chess offered an opportunity to experiment on

extended

sequences of text,

often consisting of hundreds of char-

acters, that make up complete games.

The exercise had two cooperating purposes: the first au-

thor’s principal motive was to experiment with contextual

reasoning in image analysis and the second author wished

0162-8828/90/0600-0552$01

.OO

0

1990

IEEE

BAIRD AND

THOMPSON:

READING

CHESS

553

to bring

a

large fraction of the

Informant

on line to sup-

port

a

variety

of

studies in computer chess, among them

the enrichment of the opening book of Belle,

a

chess-

playing machine [4].

Section I1 describes the books in the

Chess

Informant

series. Page layout analysis is discussed in Section 111.

Classification, word segmentation, and baseline-finding

are discussed together

in

Section IV. A method to cope

with broken, touching, and dirty shapes is discussed in

Section V. Extracting games and moves using layout ge-

ometry and syntax is described in Section VI. Use of the

rules of chess to detect and correct classification errors is

described in Section VII. Performance statistics are sum-

marized in Section VIII. Systems engineering aspects are

discussed, finally, in Section IX.

11. THE CHESS

INFORMANT

The

Chess

Informant

[5] is

a

series

of

volumes describ-

ing chess games selected by an international editorial

board for their theoretical interest. Over 40 volumes have

appeared, and continue to appear at the rate of about two

a year. Each volume contains a description of about 800

games, with detailed commentary (along with indexes,

rankings lists, etc). The game descriptions are not avail-

able in computer-legible form.

An excerpt from

a

typical game description is shown in

Fig. 1. Each game is introduced by a header giving the

game number, two codes classifying the opening play, the

names of the players, the location of the tournament, and

the year.

A game description consists of

a

list of numbered moves

with commentary. Some comments are brief remarks

using special symbols, such

as

!?,

meaning

“a

move de-

serving attention,” or

f,

meaning “white has the upper

hand.” Other comments take the form of lists of alter-

native moves, enclosed in square brackets

[

- -

-].

The series is published in Beograd, Yugoslavia. The

text was set using letterpress techniques (handset lead

type) using over

200

distinct letters (see Fig.

2),

of

10

point type size.

These include complete alphanumeric fonts in both ro-

man and boldface, chesspiece characters, letters modified

with diacritical marks, and

a

set of special symbols used

for commentary. Lines of text are set solid: that is, spaced

vertically as closely as possible for the point size. The

column-break is narrow, and lines are not horizontally

aligned across it.

The quality of the paper and ink impression is variable

from volume to volume and from page to page. Uneven

inking has produced

a

wide range of character densities

and slipping type has produced gross shape distortions and

proximity effects (Fig.

3).

Other defects, including surface dirt, ink smearing, and

nonrectilinear layout

of

columns and lines, are discussed

later. Although the

Informant’s

print quality is often worse

than that seen in most modem books and journals, it dif-

fers from them more in degree than in kind of defects.

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUV

WXYZ

abcdefghi]

klmnopqrstuvwxyr

0123456789

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTLVWXY

2

~bcdcl~hiJklmoopqr~tuvwxyz

0123466789

abcd

123

’

7”S()[]/-

--=

>

<

-

r

1,

A

ec

AC

e

1618160

Us

$

i

ACRS

ftbPH**

#t

+

f

F

f

f

=

=

I

x€l0*4-/0@3=3iI\~/o

tions

Flg

2

Most

of

the distinct letter shapes occurring in the game descrip-

Fig.

3.

Distortions due

to

uneven inking, poor impressions, and broken or

tilted type.

111.

LAYOUT

ANALYSIS

Each page was scanned on

a

Ricoh IS-30 document

scanner at

a

resolution

of

300 lines per inch (12

lines/”), producing

a

binary image

of

about

8.5

Mbits,

of

which typically 800

000

are black. Maximal subsets of

%connected black pixels (‘‘blobs”) are found, typically

3000

per page. Blobs that are manifestly too large to be a

10-point character (or

a

string

of

connected characters)

are ignored.

We have found it is not necessary to examine blobs in

detail in order to analyze page layout into columns and

lines (for other approaches, see

[lo],

[9]). We simply view

each blob

as

a bounding rectangle (Fig. 4). Throughout

this analysis, we proceed strictly top-down, from coarser

partitions of the page area to finer ones (for

a

survey and

analysis of other methods, see [15]). The motive for this

is that at each step we can make decisions based on a

maximum of statistical support and with a minimum of

a

priori

assumptions.

The first step is to determine the skew angle

of

the page

as

a

whole. This is done by a recently-developed tech-

nique

[

11 that is fast and accurate to

a

resolution of

2

min-

utes

of

arc. The page is corrected for skew by “pseudo-

rotating” the boxes; each is translated

so

that the set

of

their centers rotate, but the bitmap within each box is not

rotated. This works well in practice since with ordinary

care

a

person can place

a

document on

a

scanner within

3”

of

vertical,, and such a small rotation has little effect

on character bitmaps; however, it has large effects on page

layout analysis, as we will see.

In

order to find the location of the two columns, each

box is widened slightly by

a

fixed multiple to encourage

overlapping of adjacent boxes, then projected vertically

to give a one-dimensional distribution (Fig. 5); the wid-

ening is govemed by the assumption that

a

column-break

is at least as wide

as

three em-spaces. This distribution

exhibits a small number

of

prominent plateaus which are

easily located by thresholding. The threshold is chosen to

554

IEEE

TRANSACTIONS ON PATTERN ANALYSIS AND MACHlNE INTELLIGENCE.

VOL.

12,

NO.

6.

JUNE

1990

$4

4

88'

0w.w

P.

JOOLT

"Wm

"onma

z"wm

"g=u

DPcmCsD

Fig.

6.

Schematic, exaggerated illustration of affine shear distortion of

column.layout.

&L%%

2==$%

waw

n--

Fig. 4. An image

of a

page, before skew correction. Two columns of

a

full page are on the left, and part of

the

next page appears

on

the right.

Connected components are represented

by

their bounding rectangles.

/I

Fig.

5.

The vertical projection profile

Of

the

bounding

shown

in

Fig,

7,

Schematic, exaggerated illustrations

of

laid

at

differ.

ent skew angles.

Fig. 4, after skew correction.

be the 8th percentile value of the histogram of values in

the distribution. Due to the narrowness of the column-

break, this technique would fail

if

the skew estimation

were in error by as little as 1.0" of arc. This problem is

compounded by a printing defect:

it

is possible for the

columns to be distorted by an affine shear of as much as

0.5"

(illustrated schematically in Fig. 6). Shear correc-

tion using the best alignment angle discovered among

roughly-vertical angles effectively solves this problem.

Before proceeding to find lines in each column, it is

necessary to recompute the skew angle for each, due to a

second unexpected printing defect: even when the col-

umns show no affine shear, it is possible for each to sit at

a different angle, as much as

0.6"

apart (illustrated sche-

matically in Fig.

7).

After recorrecting each column for

skew, it is possible to locate lines of text by analyzing the

horizontal projection (Fig. 8). Here a fixed threshold is

used, on the assumption that a line of text consists of at

least two characters. Break decisions are less critical than

for columns, and this technique has worked well on a wide

variety of text. However, where line-spacing is tight, it

could fail if the estimate of skew angle were

off

by as little

as

0.3"

of arc.

The contents of each line is then sorted left to right,

and, still manipulating only the boxes of blobs, characters

are tentatively identified, as collections of one or more

blobs. The rule used is to combine any pair of blobs (or,

recursively, characters) that overlap vertically by more

than

70%

of the width of either. This test

is

performed

also at a 12" slant, the typical italic inclination angle.

This works for all common fragmented characters and

diacritical marks in the text, but need not be perfect, since

it can be overruled later.

In

fact

it

succeeds on all but one

c

Fig.

8.

The horizontal projection profile of

a

column

of

text,

after

skew

correction.

of the

172

special characters in the Latin alphabet enum-

erated in the

Chicago

Manual

of

Style

[6].

IV.

CLASSIFICATION,

BASELINES,

AND

WORDS

Before attempting to locate baselines or words, we per-

form a preliminary classification of characters. The

method used is template matching.

To

match a pair of

characters, the centers of their bounding boxes are

aligned, and a bitwise exclusive-or computed. The num-

ber of nonzero bits in the result is scaled by the total area

of

both pattems and subtracted from

1

.O,

giving a match

score in the range [0,1], with 1.0 indicating a perfect

match. This is a simple implementation of a long-estab-

lished technique

[

121.

Template-matching was selected since, having fewer

than

250

distinct lettershapes, there was no requirement

_-

I-

555

BAIRD AND

THOMPSON:

READING

CHESS

for a multiple-font classifier (but, see

[8]).

Also, many

characters suffered from fragmentation, to which template

matching

is

less vulnerable than topology-based feature-

analysis methods.

We manually collected over 1300 character samples,

about

7

per class on average, each labeled with a correct

baseline location. Classification of an unknown shape oc-

curred by essentially exhaustive matching in this data-

base, yielding a list of classes in decreasing order of match

score, which was truncated when scores fell below

0.9

of

the best. A manually-selected threshold

(0.75)

was used

to distinguish good from bad matches.

Each match determines a baseline location, and the

dominant baseline-height of each text line was chosen as

the median of the set of baseline-heights for each char-

acter’s first good match. This technique is fast and has

proven to be accurate and insensitive to commonly-

occurring problems including poor character segmenta-

tion and dirt. If skew-correction has been less accurate, a

more complex two-dimensional fitting procedure would

have been required.

Each character’s match score is then modified by re-

ducing it to the extent that the height-above-baseline dif-

fers from the mean for that class, assuming a Gaussian

distribution with the standard error of the training sam-

ples. This final match score thus depends primarily upon

similarity of shape, and secondarily on vertical placement

in the line. In this application, baseline displacements as

small as 1/5 of the x-height of the font can be crucial,

since this distinguishes between the square brackets

‘[’

and

‘I’

and similar shapes such as ‘I’ and

‘J’.

The brackets

are important lexical break characters used to extract

games and ignore commentary.

Text lines are partitioned into words by examining the

statistics of intercharacter spacing within each column. A

histogram of intercharacter distances usually possesses a

bimodal distribution whose minimum makes a good

threshold for distinguishing word- from character-spaces.

In practice, the histograms tend

to

be sparse and badly-

behaved. By quantizing coarsely (by 1

/6

of an em-space),

and requiring the threshold to lie within a narrow range

([0.2,

0.51

em), the results are usually good.

Most residual word-segmentation problems are caused

by characters with extreme kerning properties, such as pe-

riods and wide chess-piece characters.

No

attempt was

made to exploit special knowledge of kerning. Results

were sufficiently good to serve an important function dur-

ing the “clean-up” processing described next. The final

syntactic and semantic analysis does not depend on word-

breaks at all.

Graphics such as board diagrams were either discarded

earlier as too large or appear now as a line dominated by

very bad matches; these lines are detected and ignored.

V.

FRAGMENTS,

SMEARING,

AND

DIRT

There are three ways in which the character-finding

heuristic described above can fail: 1) a character can be

fragmented;

2)

two or more characters can touch; and 3)

(a)

(b)

(C)

Fig.

9.

Defects causing problems that are resolved after preliminary clas-

sification:

(a)

touching characters;

(b)

broken characters; and (c) dirt

fragments.

stray ink marks, paper defects, or dirt can be mistaken for

a character. Of course, any combination of these can oc-

cur together. Examples of each are shown in Fig.

9.

In

virtually every instance, these problems cause a bad

match.

We observed that it was never necessary to reach across

a word-break to fix such a problem. The average length

of a word is three characters, and only

7.4%

of words on

average have at least one character with a bad match. This

suggested a strategy for correcting these defects in a un-

ified way by a nearly-exhaustive examination of altema-

tives generated within the bounds of individual words. An

outline of the heuristic is as follows:

for

each bad word

(7.4%)

{

repeat

{

try merging sets of adjacent characters (0.3

%)

for

each bad character

{

try splitting into two (or more)

(0.9%)

if

character is dirt,

then

delete it

(0.6%)

,

1

if

word is isolated dirt,

then

delete it

(0.2%)

1

until

word is deleted or not improved

1

Improvement in a word is defined as an increase in a com-

posite word-match score, computed

as

the average of the

character-match scores, weighted by area. About half of

the bad words are improved by the heuristic. The per-

centages shown for each statement are for tries that suc-

ceed in improving the character or word, expressed as

fractions of the total number, good

and

bad.

A

character is considered to be

dirt

if

it

has a low match

score

(

<0.30) and a small area (smaller than about two

periods). A word is

isolated dirt

if it consists of one dirt

character. These rules catch almost all cases, failing when

the dirt is attached to a character (Fig.

10)

or lies

so

close

to the baseline that it resembles a period. Deleting dirt is

delayed until everything else has been tried, since it can-

not be undone.

In an attempt to recombine fragmented characters, an

exhaustive list of strings of adjacent characters

is

gener-

ated. Each list is anchored at a particular bad character,

and all strings are generated that reach no further than

0.5

em from the anchor, and are no more than

1.1

em wide.

When splitting characters, a modification of Kahan’s

method

[8]

is used to purpose a small number of candidate

splitting points.

Although runtime of the heuristic is potentially expo-

556

IEEE

TRANSACTIONS ON PATTERN ANALYSIS AND MACHINE INTELLIGENCE. VOL.

12.

NO.

6.

JUNE

1990

s

Fig.

10.

Dirt fragment touching a character.

nential in the length of the word, the low frequency of

bad words and the short average length of words holds it

to about

1/7

of the cost of performing the preliminary

classification, on average (with a large variance).

VI.

EXTRACTING

GAMES

AND

MOVES

The result of the preceding stages of computation is a

hierarchical analysis of the page into columns, lines,

words, and characters, with each character owning a list

of interpretations. A sample of a galley proof format of

this data structure

is

shown in

Fig.

11,

showing only the

top choice interpretation of each character.

A

more de-

tailed format, including each character’s bounding box

and interpretation list, is shown in Fig.

12.

The results on

a sequence of pages (in detail) are concatenated and passed

to the stages that apply chess knowledge.

The text from the character recognizer is examined for

chess semantics with the goal of decoding the game played

along with players, event name and who won. The anal-

ysis is performed in sequential phases as described below.

There is no feedback between phases.

Isolating the game.

Each line is examined and classi-

fied as potentially being one of the three title lines of a

game. The first line (index) is left and right justified with

a large space in the middle. The left part has numbers

while the right part contains parentheses. The second line

(players) is centered with a hyphen or dash. The third line

(event) is centered. Whenever two or three consecutive

lines are classified into potential title lines, the previously

collected lines are analyzed as a complete game and sub-

sequent lines are collected for the next game.

Stripping Comments.

Comments are delimited by

[

*

]

brackets. For this analysis brackets are matched

in pairs. When a pair of brackets are found the following

possibilities are recognized.

[...

]

The

[

is accepted as real.

[

*

[

If the character match scores of both brackets

are above a “good” threshold, the intervening

text is examined by

reverse typesetting

(de-

scribed below) for the best potential

].

The

[

and the invented

]

are accepted as real. Oth-

erwise, the better

[

is accepted and the other is

rejected as dirt.

I...

1

By analogy with

[

*

[.

The beginning of the game is treated as if it contains a

perfect

],

while the end contains a perfect

[.

The above

COLUMN

1

1.1

lop

108:

(R

76ia)

A

62

1.2

1%

KORTCllNOl- TRINCOV

1.3

lop

Luzern

(01)

1982

1.4

lop

I.

d4 Qf6

2.

c4 e6

3

QO

c5 4. d5 ed5

1.5

lop

5

cd5

d6 6.

&3

g6

7.

g3

Pg7

8.

Pg2

1.6

lop

1.7

lop

1.8

Io0

a4 Re4

13.

Hcl bS!

14

Eel

Hb8

15.

Rd2

W

9

0-4

&6!?

10.

h3

[IO.

e4 Pg4=]

&7

[RR

10.

. .

He8!?

11.

Qf4

Oc7

12.

1.9

16

@!

76. Qdeigf4

17.

abTf5

IF,

Qd2

fg3

1.10

lop

19.

fg3

eg5

20.

Qfl

Ob5F

Csom

-

Sub&

1.11

lop

B&le

Herculane

1982;

11.

bd2!”]

11.

e4

Fig.

I

I.

Galley proof format. used

for

manual proofreading,

for

the game

fragment shown in Fig.

1,

Each line is labeled with the point size.

1.0601 1.5531

1.1231

1.6511

1

9 0.90

1.1371 1.617i

1.1631 1.6471

1

per

0.95

1.2201 1.5401

1.5001 1.6771

0

\O

1.545n

1.2201 1.5501

1.2871 1.6431

1

0 0.93

1.2971 1.6001

1.4271 1.6201

1

dsh

0.94

1.4331

1.5501 1.5001

1.6431

1

0

0.93

1.5601 1.5401 1.9631

1.6771

0

\O

1.636”

1.5601 1.5401 1.6831

1.6671

1

chN

0.90

1.703i 1.5771

1.7701

1.6431 4

a

0.90

n

0.85

U

0.84

s

0.83

1.7801

1.5471 1.8431

1.6471

1

6

0.91

1.8701 1.5471 1.8871

1.6431 2

ex

0.90

1

0.81

1.9171

1.5471 1.9631

1.647i

1

qm

0.92

3.0331

1.5401 a.2031

1.6771

o

\o

i.9ogn

2.0331

1.5431

2.0871 1.6431

4

1

0.91

I

0.83

1-sl

0.83 i 0.82

2.1001 1.547i

2.1631 1.6431

1

0

0.95

2.1731 1.6171

2.2031 1.6431

1

per

0.92

2.2601

1.5401 2.4131

1.677i

0

\O

1.545n

2.2601

1.5431 2.3431

1.6471 2

h

0.94

b

0.89

2.3471

1.5471

2.4131 1.6471

1

3

0.89

Fig.

12.

Detailed layout description of moves

9

and

10

of the game shown

in Figs.

1

and

11.

The four coordinates on the left describe bounding

rectangles. The next number

is

a code

n

:

if

n

=

0,

then this is a layout

feature, such as words (labeled

“\O”)

or

text lines (not shown);

if

n

>

0.

then it is a character possessing

n

interpretations. Each interpretation

consists of a letter-name and a match merit (e.g., “chN

0.90”

is a chess

knight with merit

0.9).

algorithm accepts, rejects, and invents brackets

SO

that

they are balanced. Accepted brackets and their enclosed

text are discarded as commentary. This eliminates about

50%

of the characters from further analysis. It is good at

locating brackets that were typeset but are unrecognizable

due to printing defects, but is not at all good at supplying

brackets that were omitted by the printer. The text con-

tains lots of clues for real missing brackets, such as re-

peated move numbers, change in type face, commentary,

etc; none of this is used.

Sketching the move sequence.

The text is examined for

move numbers in sequence. The test is rigorous enough

so

that any numbers less than almost perfect are deferred

until a later phase.

Interpreting the game result.

The next after the last

move number is examined by reverse typesetting for one

of: 1-0 (white wins),

0-1

(black wins), or

l/2-1/2

(draw).

Completing the move sequence.

Missing numbers in the

move sequence are filled in by reverse typesetting. Pos-

sibly missing numbers between the last backbone number

and the result are similarly filled in.

Preparsing the

moves.

The text between move num-

bers is examined for two syntactically-correct chess ply,

one for White and one for Black. Candidate ply are as-

sembled from the alternatives offered by the classifier.

Correct forms of a ply include Piece-Letter-Digit (PLD),

LLD, LD, PLLD, PDLD, or castle. A piece is one

of

I3

43

a

6,

a letter

abcdefgh,

a digit

12345678,

and

castle either

0-0

or

0-0-0.

Commentary characters

may occur after each ply, outside of brackets; these are

BAIRD AND

THOMPSON:

READING

CHESS

551

recognized and discarded. If one or more correct candi-

dates are found for

both

ply, then they are recorded and

the text is never interpreted again. When there is more

than one candidate, they are sorted decreasing on the

product of the match scores (i.e., classifier’s top choices

first). These

preparsed

moves comprise about 98

%

of the

total moves.

Reverse typesetting

is the use of the bounding rectangle

of characters to prune lists of matches. Both height and

width of boxes are compared, but not height above base-

line. It is never required when pruning lists from the clas-

sifier, but it is helpful when scanning for missed brackets

or eliminating wild choices made by the move generator.

VJI.

CORRECTING

MOVES USING

SEMANTICS

Preparsed moves are interpreted in the current chess

context and, if legal, the move is made and the match

continues. If the preparsed move is illegal the match is

terminated. If the move is not preparsed, then we have

reached an

impasse,

and all legal next moves from the

current board position are generated and pruned using re-

verse typesetting. The potentially exponential runtime of

this exhaustive step is managed by taking the product

of

the scores

of

the matched moves and pruning below a

threshold. All matches above threshold are made and

matching continues in a depth-first, best-match-first man-

ner. The first longest match is taken as the game score.

It is conceivable that some game interpretation could

be legal and still differ from the clear intention of

the

ed-

itor-but such forced interpretations have not been ob-

served. An example of the results of semantic analysis are

shown in Fig.

13.

The text that represents the players and event are

matched against (separate) dictionaries of names. A larg-

est substring algorithm is used to find the closest name in

the dictionary. The scores for the matches are recorded

on an error file and examined by hand for additions to the

dictionaries. The dictionaries are initially created from the

index in the

Informant.

This is highly redundant between

issues with only about

5%

new entries per volume after a

two volume startup.

VIII.

RESULTS

Among the first 142 games, two were rejected by the

system for typographical errors. Three others could not

be corrected by the semantic analysis. The rest, 98% of

the typo-free (correctly-printed) games, were accepted by

the semantic analysis, and have been proofread by hand

to confirm the interpretation.

No

forced interpretations

(substitution errors) were found. If game interpretations

were selected from those that could be assembled from

the top three classifier choices (with syntactic but no se-

mantic analysis) this fraction falls to

76%.

Interpretation

by shape alone (using only the classifier’s top choices)

would have yielded 40

%

of the games completely correct,

for an error rate a factor of

30

worse than that achieved

by semantic analysis.

One of the games that could not be fully corrected had

/

person: TRINGOV (Trinqov

-0)

/

person: KORTCIINOI (KOrtchnOi

-2)

white: Kortchnoi

black: Tringov

/

event: Luzernlol)1982 (Lurcrn

(01)

1982

-0)

event: Lurern (01) 1982

result: 1-0

a4

Nf6 c4 e6 Nf3 CS d5 e:d5 c:d5 db

Nc3

q6

93

%37

%32

0-0

0-0

Nab h3 Nc7

e4

Nd7 Bf4 Qe7

Re1

f6 Nh2 Rb8

Be3

b5

f4 b4 NA~ Nb5 Rc1

Re8

Nf3 Of8 Bf2

Bb7

Bfl Nc7 Nd4

Kh8

Nc6 RA8 N:b4 f5

e5

d:e5

Of3 N:b4 O:b? Nd3

B:d3

Q:g3r

-2

Q:d3 Rcdl Ob5

b4

Race

Qd5

0.36

Bc5 QA4

e6

Qd3

Rd3 Ob2

e?

A6

QC6

class/

004

108.*lR76/a)A62

N:CS N:CS

B:CS

of7

~d6

~:d5

0c4

Of6 f:e5

w5

Fig.

13.

Results ofthe syntactic and semantic analysis

for

the game open-

ing shown in Figs.

1,

11.

and

12.

Note that move numbers and com-

mentary have been stripped

off

and a player’s name has been corrected.

The opening classification

“(R76/a)A62”

has been recomputed.

garbled characters at the very end, where there was no

later context from which to backtrack. Another had too

many consecutive impasses, at the outset of a game, lead-

ing to an unmanageably large search space. The line of

text involved

is

illustrated in Fig.

14.

The top line is the

bitmap (after cleaning up dirt), and the bottom line the

top-choice interpretations by the classifier. Bad matches

are marked with surrounding boxes.

For 99.4% of the ply, at least one candidate suggested

by the classifier was syntactically correct. Of these, the

top choice was semantically legal 98.7% of the time.

About

0.5%

of

the ply were associated with impasses,

and the final correct rate among ply after semantic anal-

ysis was 99.99%. Since ply are made of about three char-

acters on average, the effective per-character success rate

is probably better than 99.995

%

.

We have no direct mea-

surement of the uncorrected character recognition rate,

and it is difficult to infer it in an unbiased way since,

among other problems, about half

of

the characters are

ignored as commentary.

We have continued reading-without manually proof-

reading every game-and after four volumes (945 pages,

2850

games,

2

176

865

characters) performance is hold-

ing steady, with legal interpretations found for over 97%

of the games free from typographical errors. Since about

a million of these characters occur in commentary, the

semantic analysis was applied to about a million charac-

ters for an effective rate of successful interpretation of

99.995%.

The system was written entirely in the

C

programming

language and ran under various research editions of the

UNIX@ operating system. Runtime for the image analysis

phases averaged

10

CPU minutes per page on a DEC

VAX@ 11/8550, of which

87%

was consumed in exclu-

sive-or operations during template matching. Connected

components analysis and layout analysis required about

10

CPU seconds apiece. Resegmentation of dirty, etc.

shapes required an average of one CPU minute, with a

moderately large variance due to variations in image qual-

ity from page to page. The syntactic and semantic anal-

ysis was performed on a Sequent; CPU time averaged

2

WNIX

is a registered trademark

of

AT&T.

WAX

is

a

registered trademark

of

Digital Equipment Corporation

558

IEEE TRANSACTIONS

ON

PATTERN ANALYSIS AND MACHINE INTELLIGENCE.

VOL.

12.

NO.

6.

JUNE

1990

1.

d4

Qf6

2.

cl

c3

3,

dS

b3

I.

a‘3

1.

d4

mf6

2.

cl

e3

3.

da

bl

1.

mrl3

Fig. 14. A line of text containing enough impasses to induce failure of the

semantic analysis. The top line is the original bitmap, after dirt frag-

ments have been deleted, sometimes erroneously

(as

in

“f”).

The bot-

tom line shows the classifier’s top choices, with bad matches enclosed

in boxes.

seconds per game, but of course with a large variance

since several games required up to one CPU minute and

a few (not averaged in) never terminated normally.

IX.

DISCUSS~ON

The

Chess

Informant

is an unusual object of machine

vision in that its content has effectively- and efficiently-

computable semantics. The remarkably high competency

achieved by exploiting this fact should encourage further

attacks on images with similarly conventional, unambig-

uous

consistency constraints.

In other respects, however, the

Informant

is represen-

tative of a broad class of printed documents. Nonrectili-

near layout, tight column- and line-spacing, and broken,

touching, or dirty character-images all occur in other doc-

uments. For this reason, we believe that several of the

methods first applied here will be useful in achieving high

performance in the general case.

The layout analysis approach

is

unusual in following a

strictly top-down policy. Relying on a minimum of

a

priori

assumptions, it is characterized by a sequence of

refinement steps ordered

so

that the broadest statistical

support may be applied to the inference of layout param-

eters.

So,

for example, text line orientation is estimated

from evidence distributed over the whole page, word-

break spacing over each column, and baseline is deter-

mined by consensus within entire text lines. The success

of this strategy, without recourse to backtracking, in the

face of manifold layout distortions is largely due to the

accuracy of the skew-finding method.

We attempted to base as much

of

the error management

as possible on a single robust measure of merit. The clas-

sifier’s template match score, occasionally modified (by,

e.g., height above baseline) or combined (to score words

and ply), was used to control virtually all later analysis.

The attempt to apply semantic interpretation to long se-

quences of text ran a substantial risk of intolerable run-

times due to combinatorial explosion. Without a basis of

consistently good results from the early states of layout

analysis and character-shape recognition, the effort would

have collapsed.

A striking feature of the engineering design is a pro-

gression from fast heuristics in the early stages to slower

and more exhaustive algorithms at the end. For example,

it is not until text has been segmented into words that a

nearly-exhaustive search is unleashed to fix broken,

touching, and dirty characters. Full backtracking is re-

served for the last stage of semantic processing after sev-

eral kinds of global and local context has been applied to

prune interpretations to a manageable number.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

An earlier version of the paper appeared as

[3].

The

character-splitting heuristic was a variant of one devel-

oped by

S.

Kahan. The UNIBUS interface for the Ricoh

scanner was designed by

J.

Condon and built by W. Moy.

Its UNIX driver was written by

L.

Cherry.

REFERENCES

[I]

H.

S.

Baird, “The skew angle

of

printed documents,” in Proc. SPSE

40th Con$ Symp. Hybrid Imaging Systems, Rochester, NY, May

121

W.

W.

Bledsoe and I. Browning, “Pattern recognition and reading

by machine,” in 1959 Proc. Eastern Joint Computer Conf., 1959.

131

H.

S.

Baird and K. Thompson, “Reading chess,” in Proc. IEEE

Comput. Soc. Workshop Computer Vision. Miami Beach, FL, Nov.

30-Dec. 2, 1987.

[4] J.

H.

Condon and K. Thompson, “Belle,” in Chess Skill in Man and

Machine, P. Frey, Ed.

[5] Chess Informant. vols. 29, 30, 33. Beograd, Yugoslavia: Sahovski

Informator. 1980- 1982.

[6] The Chicago Manual of

Style.

13th ed. Chicago,

1L:

University of

Chicago Press, 1982, p. 254.

[7]

J.

J.

Hull.

and

S.

N.

Srihai-i, “Experiments in text recognition with

1987, pp. 21-24.

New York: Springer-Verlag, 1982.-

binary n-gram and Viterbi analysis,”

IEEE

Trans. Pattern Anal. MA-

chine Intell.

,

vol. PAMI-4, pp. 520-530, Sept. 1982.

S.

Kahan,

T.

Pavlidis, and

H.

S.

Baird, “On the recognition

of

printed

characters

of

any font and size,” IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Machine

Intell.,

vol. PAMI-9, no. 2,

pp.

274-288, Mar. 1987.

H.

0.

Kida,

0.

Iwaki. and

K.

Kawada. “Document recognition sys-

tem for office automation.” in Proc. 8th

Inr.

Con$ Pattern Recog-

nition. Paris. France. Oct. 1986.

pp.

446-448.

E.

Meynieux,

S.

Seisen, and

K.

Tombre, “Bilevel information cod-

ing in office paper documents,” in Proc. 8th

Int.

Con$

Pattern Rec-

ognition, Paris, France, Oct. 1986, pp. 442-445.

W.

S.

Rosenbaum and J. J. Hilliard, “Multifont OCR postprocessing

system,”

IBM

J.

Res.

Develop.,

vol.

19,

pp.

398-421, July 1975.

H. F. Schantz, The History of OCR, Recognition Technologies Users

Assoc., 1982.

S.

N. Srihari,

J.

J. Hull, and R. Choudhari, “Integrating diverse

knowledge sources in text recognition.” ACM Trans.

Ofice

Inform.

S~sr.,

vol.

I,

pp.

68-87, Jan. 1983.

R. Shinghal, and G. T. Toussaint, “Experiments in text recognition

with the modified Viterbi algorithm,” IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Ma-

chine lnte/l., vol. PAMI-I, pp. 184-193, Apr. 1979.

S.

N. Srihari and

G.

W.

Zack, “Document image analysis,” in Proc.

8th

Int.

Con$

Pattern Recognition, Paris, France, Oct. 1986,

pp.

434-

436.

1.

R. Ullman, “A binary n-gram technique for automatic correction

of substitution, deletion, insertion, and reversal errors in words,”

Comput.

J.,

vol. 20,

pp.

141-147, 1977.

BAIRD AND

THOMPSON:

READING

CHESS

559

Henry

S.

Baird

(M’80)

received the Ph.D. de-

gree from Princeton University. Princeton, NJ.

He is a Member

of

the Technical Staff at the

Computing Science Research Center, AT&T Bell

Laboratories, Murray Hill,

NJ.

His research fo-

cuses on algorithms for machine vision. with em-

phasis on the interpretation

of

images of printed

documents. In 1976 he gave the first complete de-

scription

of

the sweep-line algorithm,

a

funda-

mental technique

in

computational geometry and

an essential engineering component

in

the analy-

sis

of

VLSI mask artwork.

Dr. Baird is an Associate Editor of IEEE T-PAMI, and

a

member of the

Editorial Board of

Patferri

Recognition

journal. He will serve

as

Program

Chair

of

the 1990 IAPR Workshop on Syntactic and Structural Pattern Rec-

ognition. His Ph.D. thesis on algorithms for image matching won

a

1984

ACM Distinguished Dissertation Award and was published by the MIT

Press. He is a member

of

the Association for Computing Machinery and is

active

in

the IAPR.

Ken

Thompson

was born in New Orleans, LA,

in 1943. He received the

B.S.

and M.S. degrees

in electrical engineering from the University

of

Califomia, Berkeley.

In 1966 he joined the Computing Science Re-

search Center

of

Bell Laboratories where he has

worked until the present. He was involved in Bell

Laboratories’ participation in the Multics project.

In 1975, he returned to Berkeley to teach Com-

puter Science for

a

year. He is one of the principal

designers

of

the UNIX time-sharing system. He is

also

one

of

the principal designers

of

the former World Computer Chess

Champion, “Belle.

”

Mr. Thompson

is

a member of the National Academy of Science and

the National Academy of Engineering.

Could somebody provide a visual to help me better understand the steps described in this paragraph.

**Chess Informant** was founded in 1966 in Belgrade, Yugoslavia (now Serbia). Serbian chess-masters Aleksandar Matanović and Milivoje Molerović started this publication with the goal of offering the rest of the world the sort of access to chess information that was enjoyed by Soviet players at the time. In many ways they were pioneers in the development of modern chess publishing.

Garry Kasparov once said "We are all children of Informant" and then explained that his own development as a chess player corresponded with the ascent of Chess Informant's popularity.

*Edition of Chess Informant*

**Opening books** are databases of chess openings. In Computer Chess, opening books help the program decide the course of action during the beginning of the game (first 10 or so moves) when positions are very open ended and computationally expensive to evaluate. There is also an analogous database for endgame positions.

#### em unit

The *em* is a scalable unit that is equal to the current font-size. For instance, in a web document where the font size is 12px, 1em will also be 12px. The name *em* was originally a reference to the width of the capital M in the typeface and size being used.

#### Skew angle

Skew angles usually result from placing an original document at an improper angle relative to a certain axis. Skew correction of scanned document images is an important step in many of automatic recognition systems.

### Belle

Belle was a chess computer developed by Ken Thompson and Joe Condon at Bell Labs. It was the dominating chess machine in the late 70s and early 80s. In 1983, It was the first machine to achieve a master-level rating of 2250.

Belle used a brute force approach. The first version of Belle examined chess positions at about 200 positions per second. By the early 80s Belle could examine 160,000 positions per second.

+ **O-O** Castles Kingside

+ **O-O-O** Castles Queenside

*Castling move*

#### Chess Notations for computers

Fortunately nowadays computer legible notations are widespread. One of the more popular notations is PGN (Portable Game Notation). PGN is a plain text format devised around 1993 by American computer scientist Steven J. Edwards. It was first popularized via the Usenet newsgroup rec.games.chess

Here is a sample:

```

[Event "F/S Return Match"]

[Site "Belgrade, Serbia JUG"]

[Date "1992.11.04"]

[Round "29"]

[White "Fischer, Robert J."]

[Black "Spassky, Boris V."]

[Result "1/2-1/2"]

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 a6 {This opening is called the Ruy Lopez.}

4. Ba4 Nf6 5. O-O Be7 6. Re1 b5 7. Bb3 d6 8. c3 O-O 9. h3 Nb8 10. d4 Nbd7

11. c4 c6 12. cxb5 axb5 13. Nc3 Bb7 14. Bg5 b4 15. Nb1 h6 16. Bh4 c5 17. dxe5

Nxe4 18. Bxe7 Qxe7 19. exd6 Qf6 20. Nbd2 Nxd6 21. Nc4 Nxc4 22. Bxc4 Nb6

23. Ne5 Rae8 24. Bxf7+ Rxf7 25. Nxf7 Rxe1+ 26. Qxe1 Kxf7 27. Qe3 Qg5 28. Qxg5

hxg5 29. b3 Ke6 30. a3 Kd6 31. axb4 cxb4 32. Ra5 Nd5 33. f3 Bc8 34. Kf2 Bf5

35. Ra7 g6 36. Ra6+ Kc5 37. Ke1 Nf4 38. g3 Nxh3 39. Kd2 Kb5 40. Rd6 Kc5 41. Ra6

Nf2 42. g4 Bd3 43. Re6 1/2-1/2

```

There are quite a few different notations you can use to write down chess games. Many of them share similar syntax.