### TL;DR

This paper is about a 2000-year-old Roman ash urn contai...

ICP-MS is widely used in environmental monitoring, geochemistry, fo...

Wine, especially red wine, is rich in various polyphenols. Polyphen...

For ancient Romans, wine symbolized transformation and rebirth. Its...

Unlike honey or olive oil which have chemical properties that make ...

It's remarkable how this ancient burial site has remained hidden f...

Different winemaking techniques affect polyphenol content:

Macer...

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 57 (2024) 104636

Available online 16 June 2024

2352-409X/© 2024 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

New archaeochemical insights into Roman wine from Baetica

Daniel Cosano

a

, Juan Manuel Rom

´

an

b

, Dolores Esquivel

a

, Fernando Lafont

c

, Jos

´

e Rafael Ruiz

Arrebola

a

,

*

a

Organic Chemistry Department, Instituto Química para la Energía y el Medioambiente (IQUEMA), Sciences Faculty, Patricia Unit for R&D in Cultural Heritage,

University of Cordoba, Spain

b

Delegation of Historical Heritage, Museum of the City, Carmona, Spain

c

Centralized Research Support Service (SCAI), Mass Spectrometry and Chromatography Unit, University of Cordoba, Spain

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Roman wine

ICP-MS

HPLC-MS

Polyphenols

ABSTRACT

Although ancient wines adsorbed on vessel walls or their remains can be identied with the help of specic

biomarkers, no analysis of such wines in the liquid state appears to have been reported to date. Therefore, the

2019 nding in a Roman mausoleum in Carmona, southern Spain, of an ash urn roughly 2000 years old, con-

taining a reddish liquid, was rather exceptional and unexpected. An archaeochemical study of the liquid allowed

it to be deemed the oldest ancient wine conserved in the liquid state. The study used inductively coupled plasma

mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) to determine the chemical elements in the mineral salts of the wine, and high-

performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) to identify the polyphenols it contained.

The mineral salt prole and, especially, the detection and quantication of some typical polyphenols, allowed

the liquid to be identied as white wine.

1. Introduction

Rehabilitation work in a house in Carmona, southern Spain, in 2019

unearthed a collective tomb belonging to the western necropolis of

Carmo, an ancient Roman city in the Baetic region. The enclosure, 3.29

m long × 1.73 m wide, was probably a family tomb. The maximum

height of the vaulted ceiling was 2.41 m (Fig. 1a and b). The mausoleum

was dated back to the early 1st century CE (Roman et al., 2019). The left

and right wall of the entrance had eight loculi (niches) in all. Two of

them were empty while the other six each contained an ash urn, the urns

holding cremation remains and various objects typically used in burial

rituals and offerings. The urn in niche 7 contained an unguentarium and

several amber beads that were examined in previous work (Cosano et al.,

2003a; Cosano et al., 2023b). On the other hand, the urn in niche 8,

preserved in excellent condition, was a glass olla ossuaria with

M− shaped handles (Fig. 1c). This urn was inside an ovoid lead case with

the at lid bulged in the middle (Fig. 1d). Inside the urn was a reddish

liquid (a total of 5 L, Fig. 1e), which was thought to be part of the

original contents, together with cremated bone remains. Given the

religious signicance of wine in the ancient Roman world, where it was

highly symbolic and closely related to burial rituals, it is unsurprising to

nd vessels that might have originally contained wines among burial

furnishings. Consequently, the reddish liquid found in the urn might be

wine or vestiges of wine decomposed over time. In fact, according to

Vaquerizo Gil (2023), wine was usually placed together with water and

foods such as honey among burial furnishing to accompany the deceased

in their transition to a better world.

In Roman times, preventing wine decay was one of the greatest

problems faced by winemakers. However, they succeeded in extending

the useful lifetime of wine by using various additives; one of the most

commonly used of which in the Baetic region was gypsum (calcium

sulphate dihydrate, CaSO

4

⋅2H

2

O). Another way of extending the life-

time of wine in Roman times was by adding cooked musts containing

large amounts of sugars to increase the alcohol content. Alternatively,

the wine was supplied with sodium chloride, possibly to enhance its

taste. Salt is also an effective preservative and stabiliser for wine. Fino

wines currently produced in the Jerez designation of origin are probably

the most like those originally obtained in Roman Baetica.

So far, all studies aimed at the chemical characterisation of Roman

wines —or ancient wines in general— have relied on analyses of

absorbed remains (carboxylic acids and polyphenols, mainly) in various

types of vessels (Garnier et al., 2003; Blanco-Zubiaguirre et al., 2019;

Briggs et al., 2022), but never on liquids. In any case, assuring that a

sample is an ancient wine requires identifying specic biomarkers,

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: qo1ruarj@uco.es (J.R. Ruiz Arrebola).

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jasrep

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2024.104636

Received 2 April 2024; Received in revised form 28 May 2024; Accepted 10 June 2024

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 57 (2024) 104636

2

including polyphenols. The presumed oldest wine preserved in the

liquid state is ’Speyer wine bottle’, which is thought to be about 1700

years old. It is held in a stoppered bottle in the Historiche Museum der

Pfaltz (https://museum.speyer.es.de/startseite) and was found in a

tomb excavated in Speyer, a German city, in 1867. The bottle is sus-

pected to contain wine from the year 325 CE, but this assumption has

never been conrmed by chemical analysis.

In addition to water and ethanol, wine contains organic substances

such as carboxylic acids, sugars, polyphenols, and various aromatic

compounds. Wine also contains mineral salts, which are highly inu-

ential on its quality. Given that the liquid contained in the ash urn was

about 2000 years old, determining its elemental composition was of

utmost importance because any organic matter in it should either be

present in very low contents or have disappeared altogether. Therefore,

the primary aim of this work was to ascertain whether the liquid in the

urn was wine or decayed wine. For this purpose, we determined the

polyphenolic markers and mineral salts for comparison with the

composition of current wines. We also sought ethanol, which might still

be present in the wine given the good condition of the tomb and its

contents.

2. Archaeological context

Carmona is a city in the Guadalquivir valley, Western Andalusia, 30

km west of Seville. Under Roman domination in the 1st and 2nd cen-

turies A.D., the city became an important municipality (the sixth largest

Baetic location in terms of population and land area) (Caballos, 2021)

enjoying abundant wheat and olive oil resources. Carmona still retains

some buildings from that period, including the Cordoba and Seville

gates, an amphitheatre, and a necropolis that is the largest and best

conserved on the Iberian Peninsula.

Although a large portion of the ancient necropolis of Carmo lies

within the archaeological ensemble of Carmona, the Roman cemetery

was larger, so it is not unusual to uncover burial complexes while

excavating buildings for construction work in the area. In 2019, reha-

bilitation work at 53 Sevilla St. exposed the access shaft to an under-

ground enclosure. Preliminary inspection conrmed that it was the

chamber of an unlooted Roman mausoleum that had undergone little

alteration since it was built. The chamber was topped by a well-

preserved vault of voussoir stones and decorated with painted geo-

metric motifs. There were eight carved niches in the walls: six contained

ash urns and funerary objects, including a glass mosaic bowl in perfect

condition.

The access shaft, which was rectangular and 1.03 m × 0.98 m, was

Fig. 1. (a), (b) Funeral chamber. (c) Urn in niche 8. (d) Lead case containing the urn. (e) Reddish liquid contained in the urn.

D. Cosano et al.

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 57 (2024) 104636

3

excavated in the rock and heightened with an ashlar ring reaching

ground level at the top (Fig. 2). The doorway leading into the structure

was opened in the northern wall; it was 1.80 m high and nished in the

manner of a semicircular arch. The doorway was connected to the

chamber by a walkway 1.46 m long × 0.70 m wide, also excavated in the

rock that was intended to strengthen the zone where the burial monu-

ment, possibly a tower, was erected on the underground section.

The chamber was also rectangular (3.29 m long × 1.73 m wide), and

the ceiling was a canyon vault with a maximum span of 2.41 m (Fig. 1a).

The western and eastern walls contained four niches each. All surfaces

inside the chamber were coated; the oor and walls with opus signinum,

and the vault with reddish lime. The coatings were decorated with a

series of geometric motifs that was seemingly left unnished but has

remained in good condition up to the ceiling. The vault was painted with

red and ochre interwoven lines forming a grid containing empty inner

spaces. The top of the northern wall was decorated with a single,

lobulated motif in red that was only partially conserved. Unlike the shaft

and the walkway, which were carved into the rock, the presence of

chipping suggested that the chamber walls were built with ashlars and

the vault was constructed with large, dry-stacked voussoirs of alcoriza

stone (a local sandstone variety). This construction method must have

required the prior digging of a large open-air pit to erect the burial

structure.

Two of the eight niches found in the chamber (L-1 and L-2) were

empty, probably because they were placed there, whereas the other six

contained one urn each (Fig. 3). The urn found in L-3 was a limestone

box while those in L-4, L-5, and L-6 were carved in local sandstone. The

urns in L-7 and L-8 were made from glass and were housed in lead cases.

All urns contained cremated bone remains from a single individual (a

female in L-3, L-5, and L-7, and a male in L-4, L-6, and L-8). The urns in

L-4, L-5, and L-6 were partially coated with a gypsum layer and the

gypsum in the former two was used to carve the names of the deceased:

Hispanae and Senicio (Lim

´

on & Rom

´

an, 2022).

In addition to urns and bone remains, the chamber contained other

objects used in burial rituals, some in the urns themselves. Thus, the lid

to the urn in L-3 had been deliberately used to break a glass vessel,

possibly an unguentarium, seemingly as part of a ritual that has never

been documented elsewhere. Inside that urn were an iron ring and a

glass unguentarium. Between the female bone remains in urns in L-3, L-

5, and L-7 were burnt fragments of ivory sheets that might have coated

small boxes accompanying the deceased in the pyre. On the chamber

ground under urn L-5 were a ceramic jar, a thin-walled ceramic bowl,

and a peculiar glass mosaic plate that must have contained food and

drink offerings. Next to the urn in L-7 was a glass bowl containing a bag

made of plant-based fabric (possibly ax or hemp) on the bony remains.

The bowl contained three round pieces of Baltic amber (Cosano et al.,

2023b). Next to the bag was a tightly sealed unguentarium made of rock

crystal (hyaline quartz) carved like an amphorisk that contained solid-

ied remains of the perfume it once held. The unguentarium stopper was

sealed with pitch or tar and the solidied remains allowed, for the rst

time, the chemical composition of a Roman perfume to be established:

patchouli, an essential oil (Cosano et al., 2023a). The fact that the burial

chamber was almost tightly sealed allowed other organic materials such

as fabric vestiges stuck to various objects and other remains to be well-

preserved (Gleba and Rom

´

an, 2024). On a large portion of the urn in L-7

and its lid was stuck a fabric lm suggesting that the vessel was wrapped

in cloth before it was placed in its protective lead case. Finally, the urn in

L-8 not only contained bone remains and a gold ring carved with Jano

Bifronte, but it was also lled to the brim with a reddish liquid. Despite

the initial surprise, we immediately concluded that the liquid could not

have reached the inside of the urn through ooding or leakage in the

burial chamber, nor through condensation, especially when the inside of

the urn in the adjacent niche, L-7, was under identical environmental

conditions but completely dry.

The exceptionally good conservation conditions of the ensemble

allowed a valuable trousseau to be recovered. The trousseau was

comprised of high-quality pieces typical of high-standing owners;

organic materials such as liquids or solidied remains from a perfume;

fabrics and amber. All these elements are rarely preserved, so they

offered a unique opportunity for study. Based on the materials it con-

tained, and structural similarities with other burial places, the tomb was

probably used during the rst half of the 1st century CE.

3. Materials and methods

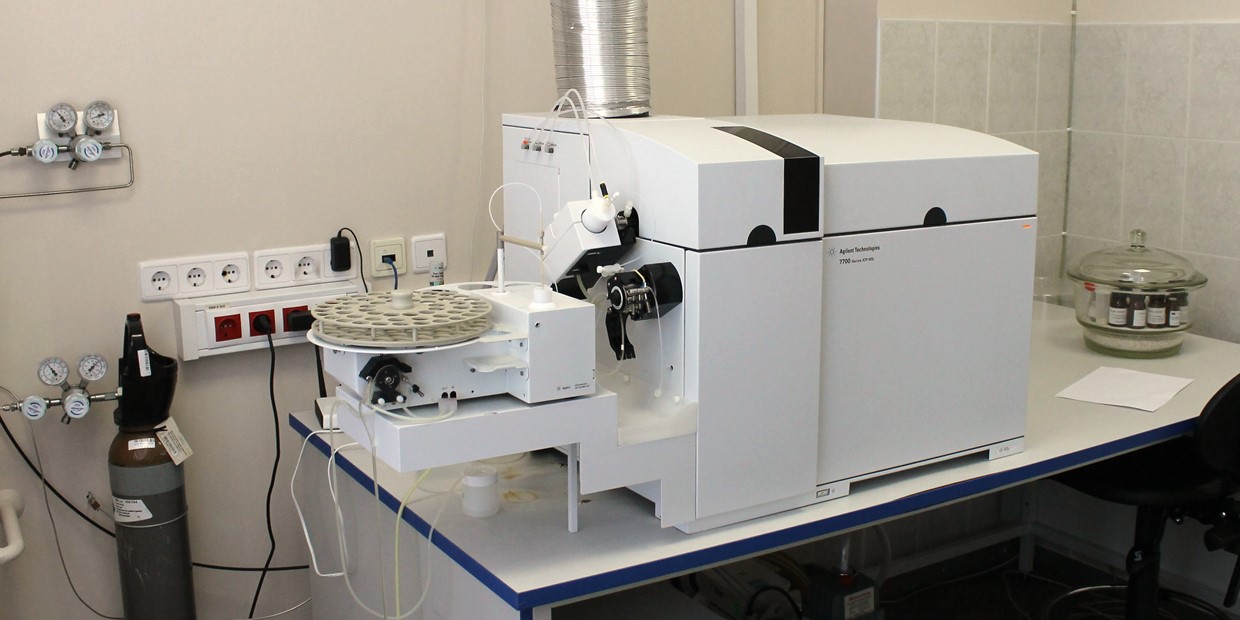

The analysis for mineral salts was performed on a PerkinElmer

NexION 350X inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer, using

samples that were previously dissolved in milliQ water containing nitric

acid. Elements were quantied relative to the internal standard with the

nearest atomic weight in the mix supplied by the instrument’s

manufacturer.

Phenolic compounds were determined by using an HPLC/MS

Fig. 2. Access to the tomb.

Fig. 3. The eight niches found in the chamber.

D. Cosano et al.

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 57 (2024) 104636

4

instrument equipped with a Sciex 7500 QTrap Triple Quadrupole ana-

lyser. Samples were diluted 25:1 with HPLC mobile phase, ltered

through paper of 0.22

μ

m pore size and directly injected onto the HPLC/

MS instrument in 2

μ

L aliquots. The HPLC conditions were as follows:

compounds were separated on a C18 phase column (10 cm long × 2.1

mm i.d., 1.6

μ

m particle size), using a mobile phase consisting of A

(water containing 0.05 % formic acid) and B (methanol containing 0.05

% formic acid), and was used in the following gradient: t = 0 min, 95 %

A; t = 12 min, 100 % B; and t = 15 min, 100 % B. The mobile phase ow-

rate was 0.40 mL/min and the column temperature 40

◦

C. Mass detec-

tion was done in the negative electrospray MRM mode, using a mini-

mum of two MRM transitions for each compound. Compounds were

quantied by external calibration against standards containing con-

centrations from 0.001 to 0.5 mg/L (linearity criteria: r

2

> 0.99 and

individual RSD < 15 %).

Ethanol was determined by GC/FID on a PerkinElmer 560 GC/FID

instrument. The sample was diluted 1:1 with water/0.01 % n-propanol

and directly analysed by GC on a Supelcowax capillary column (60 m ×

0.32 mm i.d.). The injected volume was 1

μ

L and used in the split mode

(1:20). The column temperature was isocratic (40

◦

C) and the gas

(hydrogen) passed at a rate of 2 mL/min. Ethanol was quantied against

1-propanol as internal standard.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Analysis for elements and mineral salts in the reddish liquid

The reddish liquid in the urn had a pH of 7.5, which is much higher

than that of no wines currently produced in Montilla-Moriles and Jerez

(two designations of origins coinciding with the former Baetic region),

with pH values ranging from 3.0 to 3.5. The high pH of the liquid was

suggestive of strong decay from the potential wine it once was. Also, the

proportions of carbon, nitrogen, and sulphur (0.46 %, 0.21 %, and

0.0037 %, respectively) suggested the presence of little organic matter,

which was quite plausible for strongly decayed wine by effect of the

mineralisation of organic compounds.

Mineral salts in wines come largely from the soil where vines are

grown and reach wine through grapes. Salt concentrations are typical of

each wine (Kment et al., 2005). The presence of certain metals in the

salts can result from impurities reaching the wine during production but

particularly through anthropogenic contamination (Pohl, 2007). Table 1

shows the results of the multi-element analysis conducted by ICP-MS.

The elements found were classied into three groups according to

concentration, namely: (a) elements at > 0.4 g/L. (viz., Na, K, Mg, and

Ca; G-I in Table 1); (b) elements spanning the concentration range 0.1 −

75 mg/L (B, Al, Si, Ti, Fe, Cu, Zn, Rb, Sr, Br, and Pb; G-II in Table 1); and

(c) trace elements (Li, P, V, Cr, Mn, Co, Se, Zr, Nb, Pd, Sb and others, at

even lower concentrations; G-III in Table 1). The elements in group G-I

are typically found in current wines, albeit at higher concentrations

(Kunkee & Eschnauer, 2003). Also, K is the element present at the

highest levels, whereas Ca and Mg occur at much lower, but similar,

levels, and Na has a concentration lower than one-half that of Mg.

Because they inuence its sensory properties, all metals in wine play a

crucial role (Pohl, 2007). There are few reported mineralogical

composition data for archaeological wines. Arobba et al. (2014) exam-

ined the contents of an amphora found among the remains of a ship-

wreck in the Tirreno sea occurring in the 1st century BCE The amphora

was intact, and isotopic and palaeobotanical analysis allowed the au-

thors to establish that the original content was an oenological product

produced using ancient techniques. The study was conducted on a liquid

sample extracted from the amphora, which was lled with seawater.

Therefore, the organic matter of the residue was highly deteriorated.

The elemental analysis conducted by these authors was like that ob-

tained by our study, with low carbon and nitrogen contents, indicative

of the mineralisation of organic products. The analysis of the mineral

salts reveals a composition of many elements similar to that of our

sample. The elements found at g/L levels are the same, except for po-

tassium, which in our case appears at a higher concentration. The dif-

ferences in the concentrations of elements found at levels of mg/L or

μ

g/

L can be correlated with the leaching occurring from the containers, one

ceramic and one glass, or the contribution of seawater, or the remains

contained in the cinerary urn.

The wines produced in Roman Baetica were made as described by

Columela in Book XII of his De Re rustica (Columela, 1824). As concluded

by Tchernia and Brun (1999) from the wine they made in strict accor-

dance with Roman tradition, the most similarly obtained among current

wines are probably no wines from the Jerez designation of origin. For

this reason, and based on geographic location, the mineral prole of the

reddish liquid is comparable to that of current sherry wines from Jerez,

no wines from Condado de Huelva (L

´

opez-Artíguez et al., 1996; Pan-

eque et al., 2009;

´

Alvarez et al., 2012), and no wines from Montilla-

Moriles − a designation of origin not far from Carmona (

´

Alvarez et al.,

2007a;

´

Alvarez et al., 2007b). The major elements in the wines of today

were also present in the reddish liquid. The most abundant element in

no wines is K, which was present in concentrations 2 − 3 times higher

in the reddish liquid but is rarely more than 30 % greater in current

wines. This high amount could be related to the presence of cremation

remains in the urn. The potassium content in an adult person ranges

between 120 and 140 g (John, 2015). This element is non-volatile and

remains in various salt forms in the ashes after cremation. The high

solubility in water, or in wine, of potassium salts could justify this

elevated value. The Ca, Mg and Na concentrations in the reddish liquid

also exceeded those of today’s wines. In addition, the elements typically

present at levels of a few milligrams per litre in current wines (B, Ti, Fe,

Rb, Ba, Cu, Zn, and Pb) were found at similar levels in the target liquid.

On the other hand, the Sr, Al and, especially, Si levels were higher in the

liquid. The previous differences can be ascribed to leaching from the urn

glass as well as the cremated bones also contained in the urn. As a rule,

Roman glass contained around 70 % SiO

2

, 15 − 20 % Na

2

O, and CaO and

Al

2

O

3

in proportions from 2 % to 9 %, in addition to other metal oxides

Table 1

Mineral salts composition of the reddish liquid contained in the ash urn.

Element (G-I) Concentration (g/L) Element (G-II) Concentration (mg/L) Element (G-III) Concentration (

μ

g/L)*

Na 0,43 B 3,00 Li 14

K 3,28 Al 12,41 P 14

Mg 0,94 Si 70,43 V 43

Ca 1,30 Ti 1,07 Cr 23

Fe 2,45 Mn 94

Cu 0,12 Co 51

Zn 0,29 Se 14

Rb 2,51 Zr 26

Sr 9,32 Nb 17

Ba 0,13 Pd 17

Pb 0,14 Sb 16

*

Other elements (concentration < 0,1

μ

/L): Ga, As, Y, Mo, Cs, La, Ce, Nd, Eu, W, Pt, Au, Th).

D. Cosano et al.

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 57 (2024) 104636

5

such as MgO, P

2

O

5

, K

2

O, Fe

2

O

3

, and MnO at levels around 1 % or lower

(Velo-Gala et al., 2019; Zanini et al., 2019). Therefore, the high con-

centrations of Si, Na, and Al in the reddish liquid were probably due to

leaching from the urn glass over 2000 years of contact.

4.2. Analysis of the reddish liquid for biomarkers

Polyphenols are secondary metabolites of plants encompassing a

large variety of chemical compounds with widely variable structures

that contain at least one benzene ring holding one or more hydroxyl

substituents in addition to a side chain. Grapes contain polyphenols in

amounts dependent on environmental factors such as climate and soil

nature, and grape variety, ripeness stage, and condition (Garrido and

Borges, 2013). The polyphenol composition of wine is closely related to

that of the grapes, but it additionally depends on the winemaking

method used (Fang et al., 2008). Several polyphenols are wine bio-

markers, so their presence in a sample conrms whether it is wine or

decayed wine. In fact, such biomarkers are currently used to authenti-

cate wines (

´

Alvarez et al., 2007b). This led us to examine the reddish

liquid in the ash urn in order to ascertain whether it contained poly-

phenols. To date, few studies have been conducted on polyphenols in

archaeological wine remains, and all have examined the vessels that

contained them rather than a liquid (Garnier et al., 2003; Petit-

Dominguez et al., 2003; Blanco-Zubiaguirre et al., 2019).

On average, grape pulp has a polyphenol content of 20 – 170 mg/g,

most of it in the form of phenolic acids. Anthocyans are the most

concentrated polyphenols in grape skin (500 – 3,000 mg/kg), which

additionally contains tannins and benzoic acids at the milligram per

kilogram level. On the other hand, grape seeds only contain tannins, at

concentrations from 1,000 to 6,000 mg/kg [25]. Wine contains poly-

phenols at much lower, widely variable concentrations. For example,

the polyphenol concentrations in Jerez and Montilla-Moriles wines are

usually as low as a few milligrams per litre or even lower (Benítez et al.,

2003).

HPLC-MS analysis allowed some polyphenol biomarkers to be iden-

tied in the reddish liquid, which suggests that it was originally wine but

was now highly decayed. Table 2 shows the specic polyphenols found

and their concentrations. Five were avonoids that are present in both

white and red wines. The two most concentrated avonoids in the liquid

were quercetin and apigenin, which are also those found in the highest

concentrations in today’s wines (Flamini et al., 2013). White and red

wines additionally contain substantial amounts of naringin and rutin

(Artiushenko & Zaitsev, 2023). The fth avonoid, quercetin-3-

glucoside, is a structural derivative of quercetin present in most wines

Table 2

Polyphenols composition of the reddish liquid contained in the ash urn and chemical group to which they belong.

Compound Formula Group Concentration (mg/L)

Quercetin

Flavanoids 0,09

4-Hydroxibenzoic acid

Phenolic acids 0,08

Apigenin

Flavonoids 0,05

Vanillin

Phenolic acids 0,04

Quercetin-3-glucoside

Flavonoids 0,02

Naringin

Flavonoids 0,01

Rutin

Flavonoids 0,01

D. Cosano et al.

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 57 (2024) 104636

6

(Simonetti et al., 2022). Conversely, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid and vanillin

are two benzoic acids found in all types of wine (Garrido and Borges,

2013).

The previous results, which suggest that the liquid in the ash urn was

decayed wine, were compared with the composition of current wines.

Thus, we determined the polyphenol composition of a no wine from

the Montilla-Moriles designation of origin produced in Do

˜

na Mencía, a

location in southern Cordoba near major Roman archaeological sites

such as Almedinilla, Priego de C

´

ordoba, or Torreparedones. We also

analysed two other no wines from Sanlúcar de Barrameda and Jerez.

Table 3 shows selected polyphenols found. All seven polyphenols

detected in the reddish liquid were also present in the wine from Do

˜

na

Mencía; however, rutin was not present in those from Sanlúcar de Bar-

rameda and Jerez, and quercetin-3-glucoside was also absent from the

latter. Although, as noted earlier, the polyphenols present in wine ulti-

mately depend on the grape variety and winemaking method used, most

of the polyphenols found in the current wines examined − or even all, in

some cases − were also present in the reddish liquid.

The colour of an ancient wine can be determined via another poly-

phenol: syringic acid. This acid forms by decomposition of the main

pigment in red wines, namely, the anthocyanin malvidin-3-glucoside,

which has been found in many remains from amphorae that once held

red wine (Guasch-Jan

´

e et al., 2004, Pecci et al., 2017; Fujii et al., 2019).

Its absence from the reddish liquid indicates that it was white wine

(Guasch-Jan

´

e et al., 2006), which is consistent with the writings of

Columela about white wine production in the Baetic region. However,

the colour of Roman wine is a topic that has been discussed in the

literature (Tchernia & Brun, 1999; Thurmond, 2017). In fact, in his

Natural Historia, Plinio (2010), Pliny distinguishes up to four types of

wine based on their colour: albus (pale white), fulvus (reddish-yellow),

sanguineus (blood red), and niger (black). The wine acquires these col-

ours after the fermentation process and through its storage. Thus, over

time, wine becomes darker due to oxidation reactions (Tchernia & Brun,

1999). Some varieties of ancient red grapes produced a dark-coloured

must, and these could be the origin of the black wines mentioned by

ancient authors (Brun, 2004). In general, the red colour of a wine comes

from the maceration of the must with the skin and other solid residues of

the grape, due to the release of colouring compounds called anthocya-

nins, which belong to the tannin family. The objective of maceration in

modern winemaking is to achieve a red hue in the wine. The maceration

time can last from a few hours to several days or weeks, depending on

the tannin content of the grapes and the desired nal colour (Robinson,

2006). This modern concept of maceration does not appear in classical

sources. This, coupled with the recommendation of agronomists of the

time, such as Columella, to transfer the must to dolia immediately after

pressing, has generated the idea that Roman wines were essentially

white (Brun, 2003; Harutyunyan & Malfeito-Ferreira, 2022; Aguilera

Martín et al., 2023). However, according to van Limbergen & Komar

(2024), this interpretation is subject to current standards of differenti-

ation between red and white wines, something that did not exist in

Roman times. Ancient sources also do not explicitly state the need to

remove solid remnants after grape pressing. This fact, coupled with the

identication of Vitis pollen by some authors (Arobba et al., 2014), could

indicate a certain level of maceration in some wines. In Baetica region,

wine production followed the guidelines set by Columella, who, as

mentioned previously, recommended immediately transferring the must

without allowing for maceration. This fact, coupled with the absence of

syringic acid in our reddish liquid, makes it plausible that the wine

contained in the urn was white. Chemical, physicochemical, or leaching

processes from the solid residues contained in the urn may be respon-

sible for the nal reddish colour.

5. Conclusions

The exceptional nding in an unlooted Roman mausoleum in Car-

mona, southern Spain, of an ash urn containing cremated human re-

mains and a reddish liquid that had remained intact for about 2000 years

was a unique opportunity to examine the chemical composition of the

liquid to ascertain whether it was the oldest wine in the world. The

mineral salt composition of the liquid was quite similar to no wines

currently produced in the former Baetic region. The presence in the

liquid of increased concentrations of some chemical elements can be

ascribed to leaching from the urn glass and cremated remains and sug-

gests that the liquid might be decayed wine. In fact, its elemental

analysis revealed a carbon content of only 0.46 %, which suggests strong

mineralisation of the original organic compounds. Analysing the liquid

for polyphenols typically present in current wines allowed further

insight into the identity of the liquid. The results conrmed with a high

certainty that the liquid was wine and, more specically, white wine, an

assumption strengthened by the presence of ethanol at very low con-

centration. However surprising, this result is consistent with the very

good preservation condition of the studied mausoleum. The use of wine

in Roman burial rituals is well-known and documented. Therefore, once

the cremated remains were placed in it, the urn must have been lled

with wine in a sort of libation ritual in the burial ceremony or as part of

the burial rite to help the deceased in their transition to a better world.

The results obtained in this work strongly suggest that the reddish liquid

in the ash urn was originally wine that decayed with time, and that it

was about 2000 years old, and hence the oldest wine found to date.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Daniel Cosano: Methodology, Investigation. Juan Manuel Rom

´

an:

Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization.

Table 3

Polyphenols determined in current wines. All values are expressed in ppm.

Polyphenol Montilla-Moriles Sanlúcar de Barrameda Jerez

Apigenin* 0,04 0,01 0,01

Caffeic acid 0,06 0,92 0,14

Caftaric acid 0,31 24,69 21,23

Catechin 0,07 0,06 0,05

Ferulic acid 0,04 0,08 −

Gallic acid 3,36 2,61 3,63

4-Hydroxybenzaldehyde 0,05 0,17 0,21

4-Hydroxybenzoic acid* 0,63 0,37 0,58

Vanillin* − 0,06 0,04

Hydroxytyrosol 4,07 4,22 3,37

Quercetin* 2,54 0,13 0,06

Quercetin-3-glucoside* 0,02 0,02 −

Rutin* 0,01 − −

Vanillic acid 1,48 1,18 1,23

Naringin* 0,02 0,01 −

*

* denotes the polyphenols detected in our reddish liquid.

D. Cosano et al.

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 57 (2024) 104636

7

Dolores Esquivel: Writing – original draft, Investigation. Fernando

Lafont: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Concep-

tualization. Jos

´

e Rafael Ruiz Arrebola: Writing – review & editing,

Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing nancial

interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to inuence

the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Research Group PAI FQM-346, IQUEMA

and the Central Research Support Service (SCAI) of the University of

C

´

ordoba for their help with the experimental part. They are also grateful

to the archaeologists Jacobo V

´

azquez Paz and Adri

´

an Santos Allely, co-

directors of the excavation; Research Group PAI HUM-650 of the Uni-

versity of Seville; and the owners of the excavated building (María

García and Jos

´

e Avil

´

es). D. C. acknowledges the FEDER funds for Pro-

grama Operativo Fondo Social Europeo (FSE) de Andalucía 2014-2020

(DOC_01376) and Project (PP2F_L1_07).

References

Aguilera Martín, M., Sunyer Sunyer, M., Vaquer Llop, J.M., G

´

omez S

´

anchez, J., 2023.

“Vinum Mulsum. La recuperaci

´

on experimental del vino romano m

´

as exclusivo” in De

luxuria propagata romana aetate. Roman luxury in its many forms. Arqueopress

Publishing Ltd., Oxford, pp. 368–383.

´

Alvarez M, Moreno IM. Jos A, Came

´

an AM, Gonz

´

alez AG (2007b) Study of mineral

prole of Montilla-Moriles “no” wines using inductively coupled plasma atomic

emission spectrometry methods. J Food Comp Anal 20:391-395.

´

Alvarez, M., Moreno, I.M., Jos, A., Came

´

an, A.M., Gonz

´

alez, A.G., 2007a. Differentation

of two Andalusian DO “no” wines according to their metal content from ICP-OES by

using supervised pattern recognition methods. Microchem J 87, 72–76.

´

Alvarez, M., Moreno, I.M., Pichardo, S., Came

´

an, A.M., Gonz

´

alez, A.G., 2012. Mineral

prole of “no” wines using inductively coupled plasma optical emission

spectrometry methods. Food Chem. 135, 309–313.

Arobba, D., Bulgarelli, F., Camin, F., Caramiello, R., Larchar, R., Martinelli, L., 2014.

Palaeobotanical, chemical and physical investigation of the content of an ancient

wine amphora from the northern Tyrrehenian sea in Italy. J Archaeol Sci 45,

226–233.

Artiushenko, O., Zaitsev, V., 2023. Competing ligand exchange-solid phase extraction

method of polyphenols from wine. Microchem. J. 191, 108917.

Benítez, P., Castro, R., Garcia Barroso, C., 2003. Changes in the polyphenolic and volatile

contents of “no” sherry wine exposed to ultraviolet and visible raditation during

storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51, 6482–6487.

Blanco-Zubiaguirre, L., Olivares, M., Casto, K., Carrero, J.A., García-Benito, C., García

Serrano, J.A., P

´

erez-P

´

erez, J., P

´

erez-Arantegui, J., 2019. Wine markers in

archeological potteries: Detection by GC-MS at ultratrace levels. Anal. Bioanal.

Chem. 411, 6711–6722.

Briggs, L., Demesticha, S., Katzev, S., Swiny, H.W., Craig, O.E., Drieu, L., 2022. There’s

more to a vessel than meets the eye: Organic residue analysis of ‘wine’ containers

from shipwrecks and settlements of ancient Cyprus (4th–1st century bce).

Archaeometry 64, 779–797.

Brun, J.P., 2003. Le vin et l’huile dans la M

´

editerran

´

ee antique: viticulture, ol

´

eiculture et

proceeds de fabrication. Errance, Paris.

Brun, J.P., 2004. Arch

´

eologie du vin et de l

́

huile: de la prehistoire a l

́

epoque

hellenestique. Errance, Paris.

Caballos, A. (2021): “La paulatina integraci

´

on de Carmo en la Romanidad”, in Actas del II

Congreso de Historia de Carmona, Carmona Romana, A. Caballos (ed.). Universidad de

Sevilla y Ayuntamiento de Carmona, pp. 3-17.

Columela, L.J.M., 1824. Los doce libre de agricultura.

´

Alvarez de Sotomayor y Rubio

(Translator), Madrid.

Cosano, D., Rom

´

an, J.M., Lafont, F., Ruiz Arrebola, J.R., 2023a. Archaeometric

Identication of a Perfume from Roman Times. Heritage 6, 4472–4491.

Cosano, D., Esqyivel, D., Rom

´

an, J.M., Lafont, F., Ruiz Arrebola, J.R., 2023b.

Spectroscopic identication of amber and fabric in a Roman burial (Carmona,

Spain). Vib. Spectrosc. 127, 103557.

Fang, F., Li, J.M., Zhang, P., Tang, K., Wang, W., Pan, Q.H., Huang, W.D., 2008. Effects of

grape variety, harvest date, fermentation vessel and wine ageing on avonoid

concentration in red wines. Food Res. Inter. 41, 53–60.

Flamini, R., Mattivi, F., De Rosso, M., Arapitsas, P., Bavaresco, L., 2013. Advanced

knowledge of three important classes of grape phenolics: Anthocyanins, stilbenes

and avonols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 19651–19669.

Fujii, H., Mazzitelli, J.B., Adilbekov, D., Olmer, F., Mathe, C., Vieillescazes, C., 2019. FT-

IR and GC–MS analyses of Dressel IA amphorae from the Grand Conglou

´

e 2 wreck.

J. Archaeol. Sci. Reports 28, 102007.

Garnier, N., Richardin, P., Cheynier, V., Regert, M., 2003. Characterization of thermally

assisted hydrolysis and methylation products of polyphenols from modern and

archaeological vine derivatives using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Anal.

Bioanal. Chem. 493, 137–157.

Garrido, J., Borges, F., 2013. Wine and grape polyphenols - A chemical perspective. Food

Res. Inter. 54, 1844–1858.

Gleba, M, Rom

´

an, JM. (2024) Textiles from a recently excavated early Roman tomb in

Carmona (Sevilla, Spain), in S. Spandidaki, C. Margaritis, A. Iancu (eds), Purpureae

Vestes VIII.

Guasch-Jan

´

e, M.R., Ibern-G

´

omez, M., Andr

´

es-Lacueva, C., J

´

auregui, O., Lamuela-

Ravent

´

os, R.M., 2004. Liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry in tandem

mode applied for the identication of wine markers in residues from ancient

Egyptian vessels. Anal. Chem. 76, 1672–1677.

Guasch-Jan

´

e, M.R., Andr

´

es-Lacueva, C., J

´

auregui, O., Lamuela-Ravent

´

os, R.M., 2006.

First evidence of white wine in ancient Egypt from Tutankhamun

́

s tomb. J. Archaeol.

Sci. 33, 1075–1080.

Harutyunyan, M., Malfeito-Ferreira, M., 2022. Historical and heritage sustainability for

the revival of ancient wine-making techniques and wine styles. Beverages 8, 10.

John, E., 2015. Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology, 13th Ed.

Kment, P., Mihaljevic, M., Ettler, V., Sebek, O., Strnad, L., Rohlova, L., 2005.

Differentiation of Czech wines using multielement composition - A comparison with

vineyard soil. Food Chem. 91, 157–165.

Kunkee RE, Eschnauer HR (2003) Wine, 6th Ed. Ullmann

́

s Encyclopedia for Industrial

Chemistry. Vol. 39, Wiley-VCH. Weinheim, Germany pp. 393-431.

Lim

´

on, M., Rom

´

an, J.M., 2022. Dos inscripciones in

´

editas en urnas procedentes de

Carmona (Sevilla). Epigraphica 84, 609–620.

L

´

opez-Artíguez, M., Came

´

an, A.M., Repetto, M., 1996. Determination of nine elements in

sherry wine by inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry. J. AOAC

Inter. 79, 1191–1197.

Paneque, P., Alv

´

arez-Sotomayor, M.T., G

´

omez, I.A., 2009. Metal contents in “oloroso”

sherry wines and their classication according to provenance. Food Chem 117,

302–305.

Pecci, A., Clarke, J., Thomas, M., Muslin, J., van der Graaff, I., Toniolo, L., Miriello, D.,

Crisci, G.M., Buonincontri, M., Di Pasquale, G., 2017. Use and reuse of amphorae.

Wine residues in Dressel 2–4 amphorae from Oplontis Villa B (Torre Annunziata,

Italy). J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 12, 515–521.

Petit-Domínguez, M.D., García-Jim

´

enez, R., Rucandio, M.I., 2003. Chemical

characterization of Iberian amphorae and tannin determination as indicative of

amphora contents. Microchim. Acta 141, 63–68.

Plinio (2010) Historia Natural. Libros XII-XVI; Manzanero Cano F, García Arribas I,

Arribas Hern

´

aez ML, Moure Casas AM, Sancho Bermejo JL, Translators; Biblioteca

Cl

´

asica Gredos. Madrid.

Pohl, P., 2007. What do metals tell us about wine? Trends Anal. Chem. 26, 941–949.

Robinson, J., 2006. The Oxford companion to wine, Third edition. Oxford University

Press, Oxford.

Simonetti, G., Buiarelli, F., Bernardini, F., Riccardi, C., Pomata, D., 2022. Prole of free

and conjugated quercetin content in different Italian wines. Food Chem. 382,

132377.

Tchernia, A., Brun, J.P., 1999. Le vin romain antique. Editions Gl

´

enat Livres, Grenoble,

France.

Van Limbergen, P., Komar, P., 2024. Making wine in earthenware vessels: a comparative

approach to Roman vinication. Antiquity 98, 1–17.

Vaquerizo Gil, D., 2023. Necropolis, rites and funerary world in Roman Hispania:

Reections, trends and proposals. Vinc. Hist. 12, 40–64.

Velo-Gala, I., García-Heras, M., Orla, M., 2019. Roman windows glass in Hispania

Baetica: Glass origin and manufacture study through electro microprobe analysis.

J. Archaeol. Sci.: Rep. 24, 526–538.

Zanini, R., Moro, G., Orsega, E.F., Panighello, S., Selih, V.S., Jacinovic, R., van Elteren, J.

T., Mandruzzato, L., Moretto, L.M., Traviglia, A., 2019. Insights into the secondary

glass production in Roma Aquileia: A preliminary study. J. Archaeol. Sci. Reports 50,

104067.

D. Cosano et al.

Wine, especially red wine, is rich in various polyphenols. Polyphenols in wine come mainly from grape skins, seeds, and stems. These compounds contribute significantly to wine's color, flavor, and mouthfeel.

Red wines typically have higher polyphenol content than white wines due to extended contact with grape skins during fermentation.

### TL;DR

This paper is about a 2000-year-old Roman ash urn containing a reddish liquid which was found in Carmona, Spain in 2019. This is believed to be the oldest known ancient wine preserved in liquid form. Using ICP-MS and HPLC-MS techniques, researchers analyzed the liquid's mineral content and polyphenols.

Surprisingly, despite its reddish color, the chemical profile indicated it was actually white wine, making this a unique archaeochemical discovery.

It's remarkable how this ancient burial site has remained hidden for so many centuries. It survived the fall of Rome, invasions by Vandals and Moors, the Christian reconquest, medieval times, and even the global conflicts of the 20th century.

Different winemaking techniques affect polyphenol content:

Maceration time:

- Longer maceration (contact between grape skins and juice) increases polyphenol extraction, especially tannins and anthocyanins. Red wines typically have higher polyphenol content due to extended maceration.

Fermentation temperature:

- Higher temperatures generally increase polyphenol extraction.

Lower temperatures may preserve more delicate aromatic compounds.

Pressing technique:

- Harder pressing can extract more polyphenols, particularly from seeds and stems.

Gentle pressing may result in fewer harsh tannins.

Oak aging:

- Barrel aging introduces additional polyphenols from wood, like ellagitannins.

For ancient Romans, wine symbolized transformation and rebirth. Its ability to alter consciousness was sometimes associated with spiritual experiences.

Romans believed in providing the dead with items they might need in the afterlife. Wine was considered a luxury item and a necessity for the journey to and life in the afterworld.

Unlike honey or olive oil which have chemical properties that make them more stable over extremely long periods, wine is a complex mixture of water, alcohol, acids, sugars, and various organic compounds, making it prone to chemical instability.

Over time, these components interact and change substantially. Additionally, if the wine container cracks, exposure to oxygen, even in small amounts, can cause wine to oxidize and further deteriorate.

Finally, while alcohol acts as a preservative, some microorganisms can still survive and slowly alter the wine over time.

ICP-MS is widely used in environmental monitoring, geochemistry, forensics and pharmaceuticals where precise elemental analysis is crucial.

The key advantages of ICP-MS are:

- High sensitivity: Can detect elements (including isotopes) at very low concentrations (parts per trillion or even quadrillion).

- Speed: Can perform rapid analyses of multiple elements.

Here's how it works:

- A sample, usually in the liquid form, enters the machine and gets in contact with an inductively coupled plasma (ICP), which is an extremely hot (6,000-10,000 K) ionized gas.

- The high temperature breaks down the sample into individual atoms and ionizes them, creating positively charged ions.

- The ions enter a mass analyzer, typically a quadrupole or magnetic sector. The analyzer separates the ions based on their mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio.

- A detector counts the number of ions at each m/z ratio. This information is used to determine the concentration of each element in the sample.