### Dead Reckoning

In dead reckoning the navigator finds his posit...

There still isn’t a consensus on whether the term "dead reckoning” ...

For most ships in the 16th century, the only available means of kee...

The log line is a mechanism to measure the speed of a ship. The mos...

*Landlubber* - a person unfamiliar with the sea or sailing

The poop (or stern) is the back or aft-most part of a ship.

says,

is a corruption of the old 'cfecf-uced reckoning' or 'position by

account', and is used to cover all positions that are obtained from 'the

course the ship steers and her speed through the water,, and from no

other

factors.' (The last italics are ours.) Had Master William Borough, Chief

Pilot of the Muscovy Company, and presently to be appointed to Queen

Elizabeth's Navy Board, come across this definition, he would have

picked a two-fold quarrel with their present Lordships at Whitehall. For

his use and explanation of the term is the earliest of which we have

knowledge, although it does not appear even then to have been new.

'And in keeping your dead reckoning', he wrote in 1^80 (having cer-

tainly never heard any nonsense about ded-uced reckoning) 'it is very

necessary that you do note at the end of every four glasses' (i.e. every

half-watch) 'what way the ship has made, by your best proofs to be used,

and how her way hath been through the water considering the sagge of

the sea to leewards, according as you shall find it growen: and also to

note . . . the wind, upon what point you find it then, and of what force

and strength it be, and what sailes you bear'. Borough was addressing

two experienced ship-masters, and for the old-time pilot there was cer-

tainly no quite separate 'estimated position' to be arrived at (according

to the Manual) when the D.R. position is adjusted for the estimated

effects of winds, currents and tidal streams. And the reason for this was

a very good one, namely that the speed of the ship through the water was

itself still a matter of estimate and not of measurement. The log line had

indeed very recently been invented but, as we shall presently see, it was

known only to a few, and even when known was (like all novelties)

viewed by sailors with suspicion. Most English seamen, and all foreign

pilots,

still determined the ship's way by 'pondering withall what space

she was able to make with such a winde and such direction' as a young

English Jesuit named Stevens put it, when trying to explain to his father

how the Portuguese ship in which he was travelling to Goa in 1579 was

navigated. Landlubbers aboard ship are, of course, a useful source of

information about sea-practice, because they describe all those things

that sailors themselves take for granted, although very likely they mis-

interpret what they see.

Such an observer was the German monk, Felix Faber, who in 1483

went on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, as a passenger in a three-masted

Mediterranean galley. The pilot was a man skilled in the paths of the sea,

he says, but he had with him other experienced men, astrologers and

augurs (or so Felix imagined them to be) who considered the signs of the

280

FIVE CENTURIES OF DEAD RECKONING 281

stars and the sky, formed a judgment as to the winds, and so directed the

pilot. All alike were expert in the art of judging from the look of the sky

whether it would be stormy or fair weather, taking into account also the

colour of the sea, the behaviour and movements of dolphins and flying

fish, the way that smoke rose, the lights that played on the masthead at

night, and the scintillations from the oars as they were dipped into the

water. At night, too, they could tell the hour simply by inspection of

the stars. They kept a mariner's compass set always against the mast,

besides another on the poop by which a lantern burned at night; and when

at sea they never took their eyes off the latter; there was always someone

watching it, and from time to time he sang out sweetly and melodiously,

an indication that the voyage was going prosperously, while by this

self-

same song the man at the helm was directed how to steer. Nor did the

helmsman ever move the rudder unless by his order who, up above, was

watching the compass; for it was he who discerned whether the ship

was proceeding in a straight line, on a curve or sideways. This last is not

a very seaman-like way of stating what went on, but we understand what

Brother Felix meant. And he continues with the information that besides

the 'Stella Maris' as they called the mariner's needle, naming it from

the star toward which it turned, they had other aids or instruments by

which to judge the courses of the stars and the blowing of the wind,

whereby they picked out those narrow paths of the sea

(semitae

mari-

timae) which must be followed. These aids, no doubt, were a useful

supplement to the astrologers and soothsayers (if such they were, and

not just the master's mate and the bo's'un), for they included a chart

carrying a scale and criss-crossed with

'

thousands and thousands' of lines

(as it seemed to the landsman)—in fact a Mediterranean plain chart or

portulan, on which were painted sixteen or more wind-roses, with the

rhumb lines ruled out in different colours. Every day (says the Brother)

the pilot and his assistants hung over this chart, conferring together, for

from it they could tell where they were, even when no land was

visible, and clouds hid the stars, and from it, too, they learned what course

to follow, from point to point along the 'lines'. Such in short was

navigation by dead reckoning in 1483 as observed by a tyro awed and

mystified, as all plain men then were, by the pilot's boast that he could

set course for an unseen destination, and avoid hidden dangers 'without

sight of sun, moon, or stars', helped only by a compass no broader than

the palm of his hand and a piece of painted parchment.

But to set a course was not to follow that course. The galley could not

sail close to the wind, but must tack to and fro, or 'traverse' as it was

then called, so that it was necessary to keep a traverse board or traverse

book in the steerage, and the course made good had to be worked out

from this each day and entered in the Journal. This meant that something

in the nature of

a

traverse table was required, and in fact a far-off ancestor

of Inman's tables, going back more than five hundred years, has survived

in the sailing directions which form part of Andrea Bianco's Atlas of

282 FIVE CENTURIES OF DEAD RECKONING

1436.*

And the mention of a similar table in a Genoese inventory of

1390 carries the date back farther still. Nor need such a table have even

then been a novelty, for the properties of the right-angled triangle, and

in particular the fact that the ratios which we term the sine, cosine and

tangent of any angle were constant no matter what the dimensions of the

triangle, had been familiar since the propositions of Euclid were once

more studied in the twelfth century. Bianco's table or

Toleta de

Marteloeo,

as it was termed, is a graphically determined set of

values

for the northing

(southing) and easting (westing) corresponding to a run of fixed length

(100 miles) along each of the eight quarters, points, or rhumbs of the

wind, from n\°, 22^°, 33J

0

, &c, up to 90

0

, which makes up a quadrant

of the compass. As the charts of those days were ruled in rhumbs and

showed no latitudes (which were not then observed in navigation) the

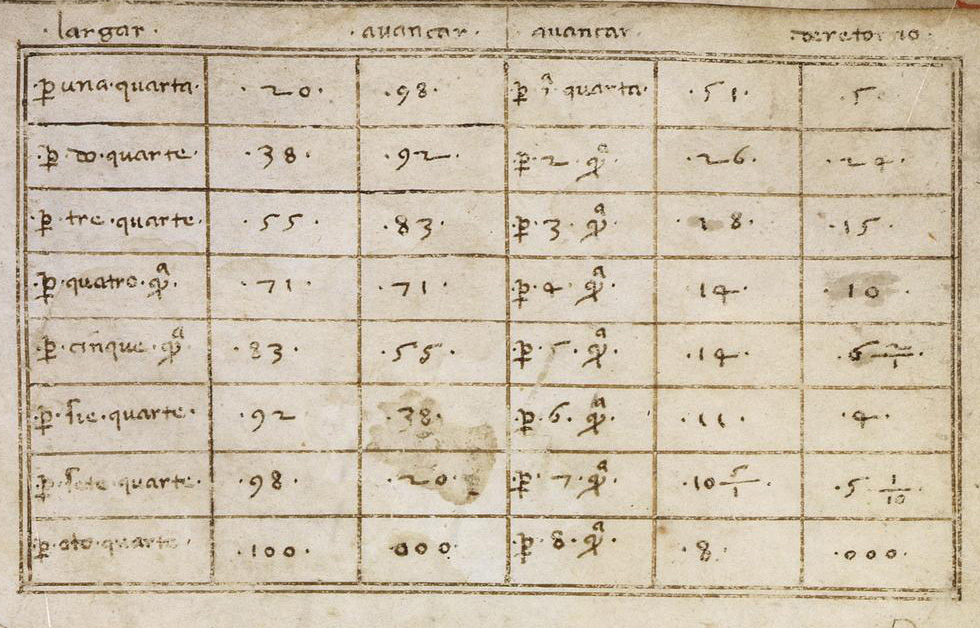

term 'd. lat.' does not appear, the columns being headed

alargar,

avancar.

According to the Toleta a ship sailing 100 miles along the sixth point

from North (67J

0

), for example, would make 92 miles easting and 38

miles northing, and so for other distances in proportion, which could be

worked out by proportion, using the Rule of Three or Golden Rule.

Even simple arithmetic was however a stumbling block to the majority,

and Bianco's Atlas also contains a scheme or diagram, constructed on

the principle of the sinical quadrant, from which a graphical solution of

the traverse could be obtained. The basis of the diagram was a large

square accurately subdivided into eight rows of eight small squares. From

the top left-hand corner were drawn the sixteen half-points and points

(beginning at

£%°)

in a quadrant. The whole was surrounded by a circle

showing the principal points of the compass. To indicate how the

diagram was to be used, a naked cherub runs along the top of the large

square, stepping off distances with a pair of dividers nearly as tall as

himself,

and opened to the width of a small square. Presumably the

diagram was intended to be drawn to the same scale as the chart and any

distance pricked off on the one could then be transferred to the other.

The northing and easting were, of course, measured directly from the

'scheme' and no arithmetic was required. With the Great Age of

Discovery, initiated by the Portuguese, long ocean voyages were begun

which required observations of latitude to check the D.R. position, and

latitudes began to be marked in the margin of the portulan chart.

Corresponding tables were eventually prepared by the Jewish mathe-

maticians responsible for working out new navigational methods, among

them the

Table

of

Leagues,

which set out the distances to be sailed along

each rhumb in order to raise or depress the pole one degree, together

with the corresponding easting or westing (departure). The degree of

the meridian was taken as 17^ leagues of 4 miles, and as an example we

can extract the following figures from the table as set out in the oldest

surviving Portuguese navigating manual: 'Item per 6 quartas releva per

grao 46 legoas e mea, at afastaras da lynha direyta 42 legoas per grao et

* It is reproduced in Fontoura da Costa's A

Marinhaiia

do

Descobrimentos

(1933).

FIVE CENTURIES OF DEAD RECKONING 283

mea.' That is to say that sailing along the 6th rhumb the distance required

to raise a degree is 46^ leagues, and the corresponding easting 42^ leagues.

The later Spanish Manuals substituted 16 and two-thirds leagues as the

measure of a degree, and the still later English manuals 60 miles, the

value used by cartographers.

As this brief review shows, seamen of four or five centuries ago would

find no difficulty in working out the daily course made good and the

position reached, provided they could make a correct estimate of the

distance sailed along each leg of the traverse. But this involved knowing

the speed of the ship, and right down to the mid-eighteenth century it was

still usual to rely on the master's or the pilot's judgment. He knew

his ship, and what she could do carrying such and such sail, under a

fresh or a light breeze, with the wind on the poop or on the quarter, and

so on. He had a rule of thumb for estimating leeway, and would help

himself at most by noting the movement of foam alongside, or by throw-

ing a chip overboard and timing its passage between two bolt-heads on

the ship's side. As to the log line, Richard Norwood, when discussing it

in his

Seaman's Practice

in 1637 declared that many sailors were either so

cocksure of their judgment that they disdained to use it, or were shamed

out of doing so because they feared to proclaim themselves 'young

seamen', that is to say inexperienced pilots.

Who invented the log line we do not know, except that he was

certainly an Englishman. The device makes its first appearance very

unobtrusively in William Bourne's

Regiment

of the Sea written about

1

£73.

The author himself was a gunner and therefore not a directly

interested party, but living at Gravesend and being interested in

'

inven-

tions and devices' of a mechanical sort he noticed what was going on.

It is he who tells us that Humfrey Cole, the famous contemporary

instrument maker, had invented a gadget to record the ship's way. But

this was not a log, it was a sort of 'way-wiser' which actually clocked up

the mileage when trailed in the water behind the ship. As for the true

log, 'to know the ship's way', Bourne says, 'some doo use this, which

as I take it is very good. They have a piece of wood, and a line to veere

out overboorde, with a small line of a great lengthe which they make

fast at one ende, and at the other end and middle they have a piece of

lyne which they make fast with a small thred to stand lyke unto a crow-

foote, for this purpose that it should drive asterne as fast as the shippe

doth go away from it, always having the line so ready that it goeth out

as fast as the ship goeth. In the like manner they have either a minute of

an hour glasse, or else a knowne part of an houre by some number of

woordes, or such other lyke, so that the lyne being veered out and

stopped just with that tyme that the glasse is out, or the number of words

spoken which done they hale in the logge or piece of wood again, and

looke how many fathoms the ship hath gone in that time.' So far there

was no question of knotting the line, and the speed had to be worked out

arithmetically, but it appears that the publicity that Bourne gave to the

284

F1VE

CENTURIES OF DEAD RECKONING

log caused more sailors to try it; and not always satisfactorily, for in a

later edition of the Regiment he adds some practical hints, in particular

that the mark on the line at which counting begins should be two or

three fathoms from the billet (later it was much more than this), so that

the log floated well clear of the dead water or eddies at the stern. He

observes that the use of

a

form of words is preferable to the minute glass,

and should be repeated two or three times if the ship is moving slowly.

No doubt the first minute (and later half-minute) glasses were not

accurately made, for such small divisions of time had hitherto hardly

been considered. Several materials besides fine sand began to be used,

including ground-up shells and particles of metal, which were thought

to run more smoothly; and Emery Molyneux, the compass and globe

maker, gained a reputation for making reliable glasses.

m l

S99, the i £87 edition of Bourne's book was translated into Dutch

and so our neighbours learned to use the log, but Fournier in his great

work on hydrography (which included navigation) published in 1643

still speaks of it as a specifically English instrument. By his day the line

had been knotted in such a way as to eliminate arithmetical calculation

and this improvement probably took place by the turn of the century,

for when Edmund Gunter, the mathematician, and Richard Norwood,

a prominent teacher of navigation, came to discuss the matter twenty or

thirty years later the stereotyped, practice was to knot the line every

7 fathoms and run it out for 30 seconds. In this way every knot run

represented approximately a mile an hour and the unit of speed became

known as the knot. The two writers mentioned were concerned, how-

ever, with the interpretation of the ship's run in terms of latitude and

longitude. It was commonly accepted that 5000 feet made a mile (7

fathoms in 30 seconds gave £040 ft. an hour), and 60 miles or 300,000 ft.

made a degree. But by the seventeenth century it was becoming more and

more apparent that the true degree was much more than 300,000 ft.

Gunter, studying the results of recent surveys accepted it as 35-2,000 ft.,

while Norwood made his own determination and arrived at the very

nearly correct figure of 367,200 ft. Neither of them wished to sacrifice

the standard '60 miles to a degree' which gave the useful relation of one

mile to a minute of arc, and both proposed re-knotting the log line so

that 'a mile an hour' actually corresponded to a minute of arc an hour,

the mile necessarily containing a greater number of feet. Gunter's method

of effecting this was to introduce a new unit, the centesme, which

measured one hundredth part of the degree of 3^2,000 ft., that is to say

o'-6 or 36 sec. of the arc.

A

little calculation will show that a line knotted

at 44 ft. intervals and run out for 4^ sec. would give the equivalent of

1 knot=

1

centesme an hour. Ten knots would be equivalent to 6 minutes

of arc an hour, g knots to 3 minutes and so on: thus runs could be

worked directly in degrees and minutes of lat. and long. (By this date

charts on Mercator's projection were available.) But Gunter

as

a landsman

did not appreciate what he was doing in throwing over the fathom and the

FIVE CENTURIES OF DEAD RECKONING 28 J

30 sec. glass, as well as introducing the still new-fangled decimal system.

It

is

true that he said that

if

the half-minute glass was retained, the line

could

be

knotted

at

29^ in., and that

all

results could

be

worked out

mechanically by the scales on his elaborate Sector, but he seems

to

have

had only one practical disciple. This was Captain Thomas James who

equipped himself with 'Gunter' sand-glasses

and

log-lines when

he

sailed in search of the North West Passage in 1631.

Norwood's degree,

it

will

be

remembered, was 367,200

ft.,

and

he

proposed to 'cast away' the odd 7,200

ft.

both because

it

left him with a

minute of arc

of

6000

ft.

and because, as he said,

it

was safer

to

have

a

method of reckoning which showed the ship

to

be nearer the land than

was actually the case rather than one which showed her farther away.

He retained

the

30'sec. glass,

but the

interval between

the

knots was

£0

ft.

and

not a

round number

of

fathoms,

so

sailors

did not

like

it.

Nevertheless

to

Gunter and

to

Norwood belongs

the

credit

of

intro-

ducing the sea mile, a unit independent of the statute mile and the older

Italian mile (of ^000 ft.), and dependent only upon an increasingly refined

measure of the degree.

Intelligent teachers

of

navigation like Captain Charles Saltonstall

advocated Norwood's line, and intelligent instrument makers like John

Seller put

it on

sale. The fact that

it

gave better results than the tradi-

tional line must have been borne

in

upon sailors, but not all were con-

vinced, as we learn from the Revd. John Harris (Secretary

to

the Royal

Society) and his disciple William Jones, both

of

whom wrote on naviga-

tion and taught its principles

in

the days

of

Queen Anne. After detailing

how the log line is run out from a reel attached to the gallery of the ship

('though this

at

best

be but a

precarious way,

'tis

however

the

most

exact

of

any

in

use') Harris gives an account

of

Norwood's measure

of

'the true Sea Mile' of 6000 ft., and his ^o ft. knot interval, and then goes

on: 'From hence plainly appears the gross Error of having but 42 feet or

7 Fathom between Knot and Knot, which

is the

common Division

of

the log-line

at

Sea. Indeed, being sensible their Divisions are too short,

they lessen their Half-minute Glass proportionably, as having that made of

only 24

or

2£ seconds. But this is nothing but correcting one Blunder or

Error

by

another, and shows plainly that

the

common Sailors will

not

go out

of

their way, tho' they are sure they are

in

the wrong.' But the

eighteenth century

was to see

changes

in all

that; nautical training

improved, time became precise, D.R. assumed its modern shape.

There still isn’t a consensus on whether the term "dead reckoning” indeed has its origins in "deduced reckoning”. The earliest known reference to this theory is in Avigation (1931) by Bradley Jones. Other alternative origins of “dead reckoning” have been proposed:

- Reckoning or reasoning (one’s position) relative to something stationary or dead in the water

- Dead in the sense “complete(ly)” (other examples: dead wrong, dead ahead, dead last)

The poop (or stern) is the back or aft-most part of a ship.

**Portulan charts** are ancient nautical charts (originally from the Mediterranean basin) with rhumb lines that radiate from the centre in the direction of wind or compass points. These charts were used by pilots to lay courses from one harbour to another.

**Example portulan chart**

A **rhumb line** is an arc crossing the meridians of longitude at the same angle.

In practice a rhumb line is what you get if you draw a straight line in the mercator projection:

If you were to look at those same lines on a globe they would look like this:

This is the diagram the author mentions:

Origin of knot as a unit of speed.

The knot is equal to one nautical mile per hour - 1.852km/h

The log line is a mechanism to measure the speed of a ship. The most basic log line consisted of a piece of wood (the log) attached to a long line knotted at regular intervals (usually knots are 14.40m apart).

In order to use it, you just throw the piece of wood to the water (while holding the long rope) and turn a 28 second sand glass. When the sand runs out, you count the number of knots that went by and that’s your speed. [Here is a video showing you how to use a log line](https://youtu.be/LZY3FJGG_gQ?t=88)

*log line*

**Bianco’s Table** (or toleta de marteloeo) was essentially a trigonometric table which helped mariners traverse from point A to point B if they weren’t traveling in a straight line between the two points. This is what Bianco’s table looked like:

In other words, this table helped mariners solve the ACD triangle in the picture below

*Landlubber* - a person unfamiliar with the sea or sailing

For most ships in the 16th century, the only available means of keeping time was a sand glass (often times, an half-hour sand glass). These sand glasses were very fragile and each ship normally carried a dozen or more.

Seamen of the period thought of time not in terms of hours but of sand glasses and watches, eight sand glasses to a watch (i.e. 4 hours). Usually crewmen would be divided into two groups or watches. Every 4 hours (eight turns of the sand glass) the men on watch would be relieved of duty by the oncoming watch.

*17th century ship’s sand glass*

### Dead Reckoning

In dead reckoning the navigator finds his position by keeping track of the course and distance he has sailed since leaving some known point (e.g. a port).

In the 15th century, course could be measured with the help of a compass and/or celestial navigation. Distance was determined by a time and speed calculation. The most accurate way of measuring time was with a sand glass (pendulum clocks would only be invented later, and were not well suited for ships due to swaying). The simplest way to measure the speed of a ship was by throwing a piece of wood over the side and recording the time it took to travel the length of the ship.