Thiel said competition is for losers, seems to be validation

#### TL;DR

The work presented in this paper is considered highly...

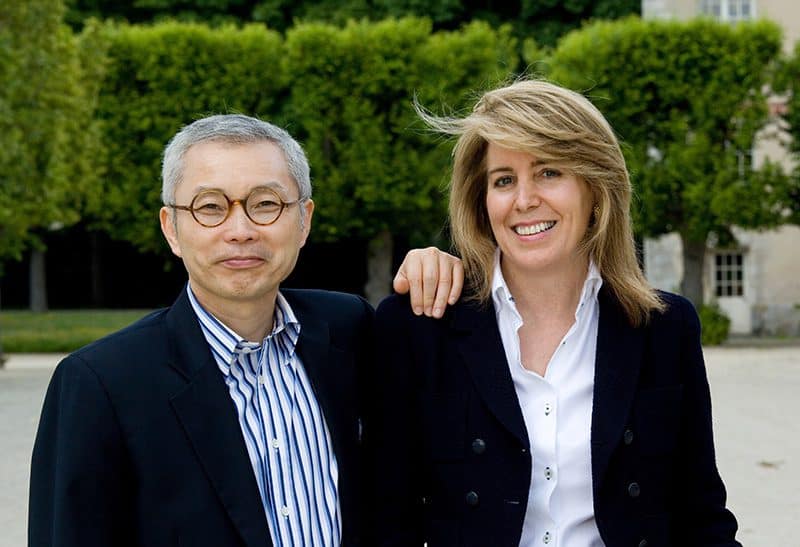

**W. Chan Kim** is a professor of strategy at INSEAD, one of the wo...

> ***"Red oceans represent all the industries in existence today—th...

Companies adopting the Blue Ocean Strategy break away from the trad...

The Paradox of Strategy

In the traditional competitive strategie...

Innovation is born out of an entrepreneur's ability to link existin...

A **common misconception is that to create a blue ocean, disruptive...

For the opposing view (i.e., incumbents *are* less likely to create...

> ***"The key is making the right strategic moves. What’s more, com...

Barriers to Imitation:

- Learning Barriers: Competitors will fac...

Blue Ocean Strategy

by W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne

harvard business review • october 2004 page 1

COPYRIGHT © 2004 HARVARD BUSINESS SCHOOL PUBLISHING CORPORATION. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Competing in overcrowded industries is no way to sustain high

performance. The real opportunity is to create blue oceans of

uncontested market space.

A onetime accordion player, stilt walker, and

fire-eater, Guy Laliberté is now CEO of one of

Canada’s largest cultural exports, Cirque du

Soleil. Founded in 1984 by a group of street

performers, Cirque has staged dozens of pro-

ductions seen by some 40 million people in 90

cities around the world. In 20 years, Cirque

has achieved revenues that Ringling Bros. and

Barnum & Bailey—the world’s leading cir-

cus—took more than a century to attain.

Cirque’s rapid growth occurred in an un-

likely setting. The circus business was (and still

is) in long-term decline. Alternative forms of

entertainment—sporting events, TV, and video

games—were casting a growing shadow. Chil-

dren, the mainstay of the circus audience, pre-

ferred PlayStations to circus acts. There was

also rising sentiment, fueled by animal rights

groups, against the use of animals, tradition-

ally an integral part of the circus. On the sup-

ply side, the star performers that Ringling and

the other circuses relied on to draw in the

crowds could often name their own terms. As a

result, the industry was hit by steadily decreas-

ing audiences and increasing costs. What’s

more, any new entrant to this business would

be competing against a formidable incumbent

that for most of the last century had set the in-

dustry standard.

How did Cirque profitably increase reve-

nues by a factor of 22 over the last ten years in

such an unattractive environment? The tagline

for one of the first Cirque productions is reveal-

ing: “We reinvent the circus.” Cirque did not

make its money by competing within the con-

fines of the existing industry or by stealing cus-

tomers from Ringling and the others. Instead it

created uncontested market space that made

the competition irrelevant. It pulled in a whole

new group of customers who were tradition-

ally noncustomers of the industry—adults and

corporate clients who had turned to theater,

opera, or ballet and were, therefore, prepared

to pay several times more than the price of a

conventional circus ticket for an unprece-

dented entertainment experience.

To understand the nature of Cirque’s

achievement, you have to realize that the busi-

Blue Ocean Strategy

harvard business review • october 2004 page 2

W. Chan Kim

(chan.kim@insead.edu) is

the Boston Consulting Group Bruce D.

Henderson Chair Professor of Strategy

and International Management at In-

sead in Fontainebleau, France.

Renée

Mauborgne

(renee.mauborgne@

insead.edu) is the Insead Distinguished

Fellow and a professor of strategy and

management at Insead. This article is

adapted from their forthcoming book

Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create

Uncontested Market Space and Make

the Competition Irrelevant

(Harvard

Business School Press, 2005).

ness universe consists of two distinct kinds of

space, which we think of as red and blue

oceans. Red oceans represent all the industries

in existence today—the known market space.

In red oceans, industry boundaries are defined

and accepted, and the competitive rules of the

game are well understood. Here, companies

try to outperform their rivals in order to grab a

greater share of existing demand. As the space

gets more and more crowded, prospects for

profits and growth are reduced. Products turn

into commodities, and increasing competition

turns the water bloody.

Blue oceans denote all the industries

not

in

existence today—the unknown market space,

untainted by competition. In blue oceans, de-

mand is created rather than fought over. There

is ample opportunity for growth that is both

profitable and rapid. There are two ways to cre-

ate blue oceans. In a few cases, companies can

give rise to completely new industries, as eBay

did with the online auction industry. But in

most cases, a blue ocean is created from within

a red ocean when a company alters the bound-

aries of an existing industry. As will become ev-

ident later, this is what Cirque did. In breaking

through the boundary traditionally separating

circus and theater, it made a new and profit-

able blue ocean from within the red ocean of

the circus industry.

Cirque is just one of more than 150 blue

ocean creations that we have studied in over

30 industries, using data stretching back more

than 100 years. We analyzed companies that

created those blue oceans and their less suc-

cessful competitors, which were caught in red

oceans. In studying these data, we have ob-

served a consistent pattern of strategic think-

ing behind the creation of new markets and in-

dustries, what we call blue ocean strategy. The

logic behind blue ocean strategy parts with tra-

ditional models focused on competing in exist-

ing market space. Indeed, it can be argued that

managers’ failure to realize the differences be-

tween red and blue ocean strategy lies behind

the difficulties many companies encounter as

they try to break from the competition.

In this article, we present the concept of

blue ocean strategy and describe its defining

characteristics. We assess the profit and growth

consequences of blue oceans and discuss why

their creation is a rising imperative for compa-

nies in the future. We believe that an under-

standing of blue ocean strategy will help to-

day’s companies as they struggle to thrive in an

accelerating and expanding business universe.

Blue and Red Oceans

Although the term may be new, blue oceans

have always been with us. Look back 100 years

and ask yourself which industries known

today were then unknown. The answer: Indus-

tries as basic as automobiles, music recording,

aviation, petrochemicals, pharmaceuticals,

and management consulting were unheard-of

or had just begun to emerge. Now turn the clock

back only 30 years and ask yourself the same

question. Again, a plethora of multibillion-

dollar industries jump out: mutual funds, cel-

lular telephones, biotechnology, discount re-

tailing, express package delivery, snowboards,

coffee bars, and home videos, to name a few.

Just three decades ago, none of these indus-

tries existed in a meaningful way.

This time, put the clock forward 20 years.

Ask yourself: How many industries that are un-

known today will exist then? If history is any

predictor of the future, the answer is many.

Companies have a huge capacity to create new

industries and re-create existing ones, a fact

that is reflected in the deep changes that have

been necessary in the way industries are classi-

fied. The half-century-old Standard Industrial

Classification (SIC) system was replaced in 1997

by the North American Industry Classification

System (NAICS). The new system expanded

the ten SIC industry sectors into 20 to reflect

the emerging realities of new industry territo-

ries—blue oceans. The services sector under

the old system, for example, is now seven sec-

tors ranging from information to health care

and social assistance. Given that these classifi-

cation systems are designed for standardization

and continuity, such a replacement shows how

significant a source of economic growth the

creation of blue oceans has been.

Looking forward, it seems clear to us that

blue oceans will remain the engine of growth.

Prospects in most established market spaces—

red oceans—are shrinking steadily. Technologi-

cal advances have substantially improved in-

dustrial productivity, permitting suppliers to

produce an unprecedented array of products

and services. And as trade barriers between na-

tions and regions fall and information on prod-

ucts and prices becomes instantly and globally

available, niche markets and monopoly havens

are continuing to disappear. At the same time,

Blue Ocean Strategy

harvard business review • october 2004 page 3

there is little evidence of any increase in de-

mand, at least in the developed markets,

where recent United Nations statistics even

point to declining populations. The result is

that in more and more industries, supply is

overtaking demand.

This situation has inevitably hastened the

commoditization of products and services,

stoked price wars, and shrunk profit margins.

According to recent studies, major American

brands in a variety of product and service

categories have become more and more

alike. And as brands become more similar,

people increasingly base purchase choices on

price. People no longer insist, as in the past,

that their laundry detergent be Tide. Nor do

they necessarily stick to Colgate when there

is a special promotion for Crest, and vice

versa. In overcrowded industries, differenti-

ating brands becomes harder both in eco-

nomic upturns and in downturns.

The Paradox of Strategy

Unfortunately, most companies seem be-

calmed in their red oceans. In a study of busi-

ness launches in 108 companies, we found that

86% of those new ventures were line exten-

sions—incremental improvements to existing

industry offerings—and a mere 14% were

aimed at creating new markets or industries.

While line extensions did account for 62% of

the total revenues, they delivered only 39% of

the total profits. By contrast, the 14% invested

in creating new markets and industries deliv-

ered 38% of total revenues and a startling 61%

of total profits.

So why the dramatic imbalance in favor of

red oceans? Part of the explanation is that cor-

porate strategy is heavily influenced by its

roots in military strategy. The very language of

strategy is deeply imbued with military refer-

ences—chief executive “officers” in “headquar-

ters,” “troops” on the “front lines.” Described

this way, strategy is all about red ocean compe-

tition. It is about confronting an opponent and

driving him off a battlefield of limited terri-

tory. Blue ocean strategy, by contrast, is about

doing business where there is no competitor. It

is about creating new land, not dividing up ex-

isting land. Focusing on the red ocean there-

fore means accepting the key constraining fac-

tors of war—limited terrain and the need to

beat an enemy to succeed. And it means deny-

ing the distinctive strength of the business

world—the capacity to create new market

space that is uncontested.

The tendency of corporate strategy to focus

on winning against rivals was exacerbated by

the meteoric rise of Japanese companies in the

1970s and 1980s. For the first time in corporate

history, customers were deserting Western

companies in droves. As competition mounted

in the global marketplace, a slew of red ocean

strategies emerged, all arguing that competi-

tion was at the core of corporate success and

failure. Today, one hardly talks about strategy

without using the language of competition.

The term that best symbolizes this is “competi-

tive advantage.” In the competitive-advantage

worldview, companies are often driven to out-

perform rivals and capture greater shares of ex-

isting market space.

Of course competition matters. But by fo-

cusing on competition, scholars, companies,

and consultants have ignored two very impor-

tant—and, we would argue, far more lucra-

tive—aspects of strategy: One is to find and

develop markets where there is little or no

competition—blue oceans—and the other is

to exploit and protect blue oceans. These

challenges are very different from those to

which strategists have devoted most of their

attention.

Toward Blue Ocean Strategy

What kind of strategic logic is needed to guide

the creation of blue oceans? To answer that

question, we looked back over 100 years of

data on blue ocean creation to see what pat-

terns could be discerned. Some of our data are

presented in the exhibit “A Snapshot of Blue

Ocean Creation.” It shows an overview of key

blue ocean creations in three industries that

closely touch people’s lives: autos—how peo-

ple get to work; computers—what people use

at work; and movie theaters—where people

go after work for enjoyment. We found that:

Blue oceans are not about technology in-

novation.

Leading-edge technology is some-

times involved in the creation of blue oceans,

but it is not a defining feature of them. This is

often true even in industries that are technol-

ogy intensive. As the exhibit reveals, across all

three representative industries, blue oceans

were seldom the result of technological innova-

tion per se; the underlying technology was

often already in existence. Even Ford’s revolu-

tionary assembly line can be traced to the meat-

A Snapshot of Blue

Ocean Creation

The table on the next page identifies

the strategic elements that were

common to blue ocean creations in

three different industries in different

eras. It is not intended to be compre-

hensive in coverage or exhaustive in

content. We chose to show American

industries because they represented

the largest and least-regulated mar-

ket during our study period. The pat-

tern of blue ocean creations exempli-

fied by these three industries is

consistent with what we observed in

the other industries in our study.

Blue Ocean Strategy

harvard business review • october 2004 page 4

Key blue ocean creations

Was the blue ocean

created by a new

entrant or an

incumbent?

Was it driven by

technology pioneering

or value pioneering?

At the time of the blue

ocean creation, was

the industry attractive

or unattractive?

New entrant Value pioneering*

(mostly existing technologies)

Unattractive

Ford Model T

Unveiled in 1908, the Model T was the first mass-produced

car, priced so that many Americans could afford it.

Incumbent Value pioneering

(some new technologies)

Attractive

GM’s “car for every purse and purpose”

GM created a blue ocean in 1924 by injecting fun and

fashion into the car

.

Incumbent Value pioneering

(some new technologies)

Unattractive

Japanese fuel-efficient autos

Japanese automakers created a blue ocean in the mid-1970s

with small, reliable lines of cars

.

Incumbent Value pioneering

(mostly existing technologies)

Unattractive

Chrysler minivan

With its 1984 minivan, Chrysler created a new class of auto-

mobile that was as easy to use as a car but had the passenger

space of a van.

Incumbent Value pioneering

(some new technologies)

Unattractive

CTR’s tabulating machine

In 1914, CTR created the business machine industry by

simplifying, modularizing, and leasing tabulating machines.

CTR later changed its name to IBM.

Incumbent Value pioneering

(650: mostly existing technologies)

Value and technology pioneering

(System/360: new and existing

technologies)

Nonexistent

IBM 650 electronic computer and System/360

In 1952, IBM created the business computer industry by simpli-

fying and reducing the power and price of existing technology.

And it exploded the blue ocean created by the 650 when in

1964 it unveiled the System/360, the first modularized com-

puter system.

New entrant Value pioneering

(mostly existing technologies)

Unattractive

Apple personal computer

Although it was not the first home computer, the all-in-one,

simple-to-use Apple II was a blue ocean creation when it

appear

ed in 1978.

Incumbent Value pioneering

(mostly existing technologies)

Nonexistent

Compaq PC servers

Compaq created a blue ocean in 1992 with its ProSignia

server, which gave buyers twice the file and print capability

of the minicomputer at one-third the price.

New entrant Value pioneering

(mostly existing technologies)

Unattractive

Dell built-to-order computers

In the mid-1990s, Dell created a blue ocean in a highly

competitive industry by creating a new purchase and delivery

experience for buyers

.

New entrant Value pioneering

(mostly existing technologies)

Nonexistent

Nickelodeon

The first Nickelodeon opened its doors in 1905, showing short

films around-the-clock to working-class audiences for five cents.

Incumbent V

alue pioneering

(mostly existing technologies)

Attrac

tive

Palace theaters

Created by Roxy Rothapfel in 1914, these theaters provided

an operalike environment for cinema viewing at an affordable

price.

Incumbent Value pioneering

(mostly existing technologies)

Unattractive

AMC multiplex

In the 1960s, the number of multiplexes in America’s subur-

ban shopping malls mushroomed. The multiplex gave viewers

greater choice while reducing owners’costs

.

Incumbent Value pioneering

(mostly existing technologies)

Unattractive

AMC megaplex

Megaplexes, introduced in 1995, offered every current block-

buster and provided spectacular viewing experiences in

theater complexes as big as stadiums, at a lower cost to

theater owners

.

Automobiles

ComputersMovie Theaters

*Driven by value pioneering does not mean that technologies were not involved. Rather, it means that

the defining technologies used had largely been in existence, whether in that industry or elsewhere.

Copyright © 2004 Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved.

Blue Ocean Strategy

harvard business review • october 2004 page 5

packing industry in America. Like those

within the auto industry, the blue oceans

within the computer industry did not come

about through technology innovations alone

but by linking technology to what buyers val-

ued. As with the IBM 650 and the Compaq PC

server, this often involved simplifying the

technology.

Incumbents often create blue oceans—and

usually within their core businesses.

GM, the

Japanese automakers, and Chrysler were es-

tablished players when they created blue

oceans in the auto industry. So were CTR and

its later incarnation, IBM, and Compaq in the

computer industry. And in the cinema indus-

try, the same can be said of palace theaters

and AMC. Of the companies listed here, only

Ford, Apple, Dell, and Nickelodeon were new

entrants in their industries; the first three

were start-ups, and the fourth was an estab-

lished player entering an industry that was

new to it. This suggests that incumbents are

not at a disadvantage in creating new market

spaces. Moreover, the blue oceans made by in-

cumbents were usually within their core busi-

nesses. In fact, as the exhibit shows, most blue

oceans are created from within, not beyond,

red oceans of existing industries. This chal-

lenges the view that new markets are in dis-

tant waters. Blue oceans are right next to you

in every industry.

Company and industry are the wrong units

of analysis.

The traditional units of strategic

analysis—company and industry—have little

explanatory power when it comes to analyz-

ing how and why blue oceans are created.

There is no consistently excellent company;

the same company can be brilliant at one time

and wrongheaded at another. Every company

rises and falls over time. Likewise, there is no

perpetually excellent industry; relative attrac-

tiveness is driven largely by the creation of

blue oceans from within them.

The most appropriate unit of analysis for ex-

plaining the creation of blue oceans is the stra-

tegic move—the set of managerial actions and

decisions involved in making a major market-

creating business offering. Compaq, for exam-

ple, is considered by many people to be “un-

successful” because it was acquired by Hewlett-

Packard in 2001 and ceased to be a company.

But the firm’s ultimate fate does not invalidate

the smart strategic move Compaq made that

led to the creation of the multibillion-dollar

market in PC servers, a move that was a key

cause of the company’s powerful comeback in

the 1990s.

Creating blue oceans builds brands.

So

powerful is blue ocean strategy that a blue

ocean strategic move can create brand equity

that lasts for decades. Almost all of the compa-

nies listed in the exhibit are remembered in no

small part for the blue oceans they created

long ago. Very few people alive today were

around when the first Model T rolled off

Henry Ford’s assembly line in 1908, but the

company’s brand still benefits from that blue

ocean move. IBM, too, is often regarded as an

“American institution” largely for the blue

oceans it created in computing; the 360 series

was its equivalent of the Model T.

Our findings are encouraging for executives

at the large, established corporations that are

traditionally seen as the victims of new market

space creation. For what they reveal is that

large R&D budgets are not the key to creating

new market space. The key is making the right

strategic moves. What’s more, companies that

understand what drives a good strategic move

will be well placed to create multiple blue

oceans over time, thereby continuing to de-

liver high growth and profits over a sustained

period. The creation of blue oceans, in other

words, is a product of strategy and as such is

very much a product of managerial action.

The Defining Characteristics

Our research shows several common charac-

teristics across strategic moves that create blue

oceans. We found that the creators of blue

oceans, in sharp contrast to companies playing

Red Ocean Versus Blue Ocean Strategy

The imperatives for red ocean and blue ocean

strategies are starkly different.

Red ocean strategy

Compete in existing market space.

Beat the competition.

Exploit existing demand.

Make the value/cost trade-off.

Align the whole system of a com-

pany’s activities with its strategic

choice of differentiation or low cost.

Blue ocean strategy

Create uncontested market space.

Make the competition irrelevant.

Create and capture new demand.

Break the value/cost trade-off.

Align the whole system of a company’s

activities in pursuit of differentiation

and low c

ost.

Copyright © 2004 Harvard Business School

Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved.

Blue Ocean Strategy

harvard business review • october 2004 page 6

by traditional rules, never use the competition

as a benchmark. Instead they make it irrele-

vant by creating a leap in value for both buy-

ers and the company itself. (The exhibit “Red

Ocean Versus Blue Ocean Strategy” compares

the chief characteristics of these two strategy

models.)

Perhaps the most important feature of blue

ocean strategy is that it rejects the fundamen-

tal tenet of conventional strategy: that a trade-

off exists between value and cost. According to

this thesis, companies can either create greater

value for customers at a higher cost or create

reasonable value at a lower cost. In other

words, strategy is essentially a choice between

differentiation and low cost. But when it

comes to creating blue oceans, the evidence

shows that successful companies pursue differ-

entiation and low cost simultaneously.

To see how this is done, let us go back to Cir-

que du Soleil. At the time of Cirque’s debut,

circuses focused on benchmarking one an-

other and maximizing their shares of shrinking

demand by tweaking traditional circus acts.

This included trying to secure more and better-

known clowns and lion tamers, efforts that

raised circuses’ cost structure without substan-

tially altering the circus experience. The result

was rising costs without rising revenues and a

downward spiral in overall circus demand.

Enter Cirque. Instead of following the conven-

tional logic of outpacing the competition by of-

fering a better solution to the given problem—

creating a circus with even greater fun and

thrills—it redefined the problem itself by offer-

ing people the fun and thrill of the circus

and

the intellectual sophistication and artistic rich-

ness of the theater.

In designing performances that landed both

these punches, Cirque had to reevaluate the

components of the traditional circus offering.

What the company found was that many of

the elements considered essential to the fun

and thrill of the circus were unnecessary and

in many cases costly. For instance, most cir-

cuses offer animal acts. These are a heavy eco-

nomic burden, because circuses have to shell

out not only for the animals but also for their

training, medical care, housing, insurance, and

transportation. Yet Cirque found that the appe-

tite for animal shows was rapidly diminishing

because of rising public concern about the

treatment of circus animals and the ethics of

exhibiting them.

Similarly, although traditional circuses pro-

moted their performers as stars, Cirque real-

ized that the public no longer thought of circus

artists as stars, at least not in the movie star

sense. Cirque did away with traditional three-

ring shows, too. Not only did these create con-

fusion among spectators forced to switch their

attention from one ring to another, they also

increased the number of performers needed,

with obvious cost implications. And while aisle

concession sales appeared to be a good way to

generate revenue, the high prices discouraged

parents from making purchases and made

them feel they were being taken for a ride.

Cirque found that the lasting allure of the

traditional circus came down to just three fac-

tors: the clowns, the tent, and the classic acro-

batic acts. So Cirque kept the clowns, while

shifting their humor away from slapstick to a

more enchanting, sophisticated style. It glam-

orized the tent, which many circuses had aban-

doned in favor of rented venues. Realizing that

the tent, more than anything else, captured

the magic of the circus, Cirque designed this

classic symbol with a glorious external finish

and a high level of audience comfort. Gone

were the sawdust and hard benches. Acrobats

and other thrilling performers were retained,

but Cirque reduced their roles and made their

acts more elegant by adding artistic flair.

Even as Cirque stripped away some of the

traditional circus offerings, it injected new el-

ements drawn from the world of theater. For

instance, unlike traditional circuses featuring

a series of unrelated acts, each Cirque cre-

ation resembles a theater performance in that

it has a theme and story line. Although the

themes are intentionally vague, they bring

harmony and an intellectual element to the

acts. Cirque also borrows ideas from Broad-

way. For example, rather than putting on the

traditional “once and for all” show, Cirque

mounts multiple productions based on differ-

ent themes and story lines. As with Broadway

productions, too, each Cirque show has an

original musical score, which drives the per-

formance, lighting, and timing of the acts,

rather than the other way around. The pro-

ductions feature abstract and spiritual dance,

an idea derived from theater and ballet. By in-

troducing these factors, Cirque has created

highly sophisticated entertainments. And by

staging multiple productions, Cirque gives

people reason to come to the circus more of-

Blue Ocean Strategy

harvard business review • october 2004 page 7

ten, thereby increasing revenues.

Cirque offers the best of both circus and

theater. And by eliminating many of the most

expensive elements of the circus, it has been

able to dramatically reduce its cost structure,

achieving both differentiation and low cost.

(For a depiction of the economics underpin-

ning blue ocean strategy, see the exhibit “The

Simultaneous Pursuit of Differentiation and

Low Cost.”)

By driving down costs while simultaneously

driving up value for buyers, a company can

achieve a leap in value for both itself and its

customers. Since buyer value comes from the

utility and price a company offers, and a com-

pany generates value for itself through cost

structure and price, blue ocean strategy is

achieved only when the whole system of a

company’s utility, price, and cost activities is

properly aligned. It is this whole-system ap-

proach that makes the creation of blue oceans

a sustainable strategy. Blue ocean strategy inte-

grates the range of a firm’s functional and op-

erational activities.

A rejection of the trade-off between low

cost and differentiation implies a fundamental

change in strategic mind-set—we cannot em-

phasize enough how fundamental a shift it is.

The red ocean assumption that industry struc-

tural conditions are a given and firms are

forced to compete within them is based on an

intellectual worldview that academics call the

structuralist

view, or

environmental determin-

ism

. According to this view, companies and

managers are largely at the mercy of economic

forces greater than themselves. Blue ocean

strategies, by contrast, are based on a world-

view in which market boundaries and indus-

tries can be reconstructed by the actions and

beliefs of industry players. We call this the

re-

constructionist

view.

The founders of Cirque du Soleil clearly did

not feel constrained to act within the confines

of their industry. Indeed, is Cirque really a cir-

cus with all that it has eliminated, reduced,

raised, and created? Or is it theater? If it is the-

ater, then what genre—Broadway show, opera,

ballet? The magic of Cirque was created

through a reconstruction of elements drawn

from all of these alternatives. In the end, Cir-

que is none of them and a little of all of them.

From within the red oceans of theater and cir-

cus, Cirque has created a blue ocean of uncon-

tested market space that has, as yet, no name.

Barriers to Imitation

Companies that create blue oceans usually

reap the benefits without credible challenges

for ten to 15 years, as was the case with Cirque

du Soleil, Home Depot, Federal Express,

Southwest Airlines, and CNN, to name just a

few. The reason is that blue ocean strategy cre-

ates considerable economic and cognitive bar-

riers to imitation.

For a start, adopting a blue ocean creator’s

business model is easier to imagine than to

do. Because blue ocean creators immediately

attract customers in large volumes, they are

able to generate scale economies very rapidly,

putting would-be imitators at an immediate

and continuing cost disadvantage. The huge

economies of scale in purchasing that Wal-

Mart enjoys, for example, have significantly

discouraged other companies from imitating

The Simultaneous Pursuit of Differentiation

and Low Cost

A blue ocean is created in the region

where a company’s actions favorably

affect both its cost structure and its

value proposition to buyers. Cost savings

are made from eliminating and reduc-

ing the factors an industry competes on.

Buyer value is lifted by raising and

creating elements the industry has

never offered. Over time, costs are re-

duced further as scale economies kick

in, due to the high sales volumes that

superior value generates.

Blue

Ocean

Buyer Value

Costs

Copyright © 2004 Harvard Business School

Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved.

Blue Ocean Strategy

harvard business review • october 2004 page 8

its business model. The immediate attraction

of large numbers of customers can also create

network externalities. The more customers

eBay has online, the more attractive the auc-

tion site becomes for both sellers and buyers

of wares, giving users few incentives to go

elsewhere.

When imitation requires companies to

make changes to their whole system of activi-

ties, organizational politics may impede a

would-be competitor’s ability to switch to the

divergent business model of a blue ocean

strategy. For instance, airlines trying to follow

Southwest’s example of offering the speed of

air travel with the flexibility and cost of driv-

ing would have faced major revisions in rout-

ing, training, marketing, and pricing, not to

mention culture. Few established airlines had

the flexibility to make such extensive organi-

zational and operating changes overnight. Im-

itating a whole-system approach is not an

easy feat.

The cognitive barriers can be just as effec-

tive. When a company offers a leap in value, it

rapidly earns brand buzz and a loyal following

in the marketplace. Experience shows that

even the most expensive marketing campaigns

struggle to unseat a blue ocean creator. Mi-

crosoft, for example, has been trying for more

than ten years to occupy the center of the blue

ocean that Intuit created with its financial soft-

ware product Quicken. Despite all of its efforts

and all of its investment, Microsoft has not

been able to unseat Intuit as the industry

leader.

In other situations, attempts to imitate a

blue ocean creator conflict with the imitator’s

existing brand image. The Body Shop, for ex-

ample, shuns top models and makes no prom-

ises of eternal youth and beauty. For the estab-

lished cosmetic brands like Estée Lauder and

L’Oréal, imitation was very difficult, because it

would have signaled a complete invalidation of

their current images, which are based on

promises of eternal youth and beauty.

A Consistent Pattern

While our conceptual articulation of the pat-

tern may be new, blue ocean strategy has al-

ways existed, whether or not companies have

been conscious of the fact. Just consider the

striking parallels between the Cirque du Soleil

theater-circus experience and Ford’s creation

of the Model T.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the

automobile industry was small and unattrac-

tive. More than 500 automakers in America

competed in turning out handmade luxury

cars that cost around $1,500 and were enor-

mously

un

popular with all but the very rich.

Anticar activists tore up roads, ringed parked

cars with barbed wire, and organized boycotts

of car-driving businessmen and politicians.

Woodrow Wilson caught the spirit of the times

when he said in 1906 that “nothing has spread

socialistic feeling more than the automobile.”

He called it “a picture of the arrogance of

wealth.”

Instead of trying to beat the competition

and steal a share of existing demand from

other automakers, Ford reconstructed the in-

dustry boundaries of cars and horse-drawn car-

riages to create a blue ocean. At the time,

horse-drawn carriages were the primary means

of local transportation across America. The car-

riage had two distinct advantages over cars.

Horses could easily negotiate the bumps and

mud that stymied cars—especially in rain and

snow—on the nation’s ubiquitous dirt roads.

And horses and carriages were much easier to

maintain than the luxurious autos of the time,

which frequently broke down, requiring expert

repairmen who were expensive and in short

supply. It was Henry Ford’s understanding of

these advantages that showed him how he

could break away from the competition and

unlock enormous untapped demand.

Ford called the Model T the car “for the

great multitude, constructed of the best mate-

rials.” Like Cirque, the Ford Motor Company

made the competition irrelevant. Instead of

creating fashionable, customized cars for week-

ends in the countryside, a luxury few could jus-

tify, Ford built a car that, like the horse-drawn

carriage, was for everyday use. The Model T

came in just one color, black, and there were

few optional extras. It was reliable and durable,

designed to travel effortlessly over dirt roads in

rain, snow, or sunshine. It was easy to use and

fix. People could learn to drive it in a day. And

like Cirque, Ford went outside the industry for

a price point, looking at horse-drawn carriages

($400), not other autos. In 1908, the first

Model T cost $850; in 1909, the price dropped

to $609, and by 1924 it was down to $290. In

this way, Ford converted buyers of horse-

drawn carriages into car buyers—just as Cirque

turned theatergoers into circusgoers. Sales of

In blue oceans, demand

is created rather than

f

ought over. There is

ample opportunity for

g

rowth that is both

p

rofitable and rapid.

Blue Ocean Strategy

harvard business review • october 2004 page 9

the Model T boomed. Ford’s market share

surged from 9% in 1908 to 61% in 1921, and by

1923, a majority of American households had a

car.

Even as Ford offered the mass of buyers a

leap in value, the company also achieved the

lowest cost structure in the industry, much as

Cirque did later. By keeping the cars highly

standardized with limited options and inter-

changeable parts, Ford was able to scrap the

prevailing manufacturing system in which cars

were constructed by skilled craftsmen who

swarmed around one workstation and built a

car piece by piece from start to finish. Ford’s

revolutionary assembly line replaced crafts-

men with unskilled laborers, each of whom

worked quickly and efficiently on one small

task. This allowed Ford to make a car in just

four days—21 days was the industry norm—

creating huge cost savings.

• • •

Blue and red oceans have always coexisted and

always will. Practical reality, therefore, de-

mands that companies understand the strate-

gic logic of both types of oceans. At present,

competing in red oceans dominates the field

of strategy in theory and in practice, even as

businesses’ need to create blue oceans intensi-

fies. It is time to even the scales in the field of

strategy with a better balance of efforts across

both oceans. For although blue ocean strate-

gists have always existed, for the most part

their strategies have been largely unconscious.

But once corporations realize that the strate-

gies for creating and capturing blue oceans

have a different underlying logic from red

ocean strategies, they will be able to create

many more blue oceans in the future.

Reprint R0410D

To order, see the next page

or call 800-988-0886 or 617-783-7500

or go to www.hbr.org

Innovation is born out of an entrepreneur's ability to link existing technology to what buyers value.

**W. Chan Kim** is a professor of strategy at INSEAD, one of the world's leading business schools, who is highly regarded for his significant contributions to the field of strategy. Kim has been recognized for his groundbreaking work on "blue ocean strategy" and he has co-written the best-selling books "Blue Ocean Strategy" and "Blue Ocean Shift."

**Renée Mauborgne** is a professor of strategy at INSEAD and co-author of the globally recognized "Blue Ocean Strategy" and "Blue Ocean Shift" books. Renée has received numerous awards for her contribution to management thinking. Her ideas have made a significant impact on the way strategy is understood and practiced in the modern business world.

#### TL;DR

The work presented in this paper is considered highly significant because it revolutionized the conventional thinking about business competition and strategy.

Traditionally, businesses focused on outperforming their rivals in established markets, fighting for a larger share of existing demand. This often resulted in cut-throat competition, lowering growth potentials and diminishing profit margins.

In this paper W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne, present a novel idea the **Blue Ocean Strategy** which breaks away from the traditional competition strategy and focuses on the creation of brand new markets - the so called "blue oceans".

The authors spent over a decade studying more than 150 strategic moves spanning more than 30 industries over 100 years (from 1880-2000). These strategic moves, which they refer to as "value innovations" were key instances where organizations departed from traditional competitive strategy (red oceans) to create new markets (blue oceans).

This work is important because it encouraged businesses to think differently, to innovate, and to explore new avenues for growth rather than merely trying to outdo competition. It has since had a significant influence on business strategy, prompting a shift towards more creative, value-driven approaches to market development.

Thiel said competition is for losers, seems to be validation

For the opposing view (i.e., incumbents *are* less likely to create blue oceans), see Clayton Christensen's *The Innovator's Dilemma*. The book is about the idea that incumbents are scared to innovate, lest their latest product undercut their main business.

In *The Power Law*, Sebastian Mallaby provides an example of how the innovator's dilemma defined the winners and losers of the personal computing revolution: "Xerox worried that a computerized paperless office would harm its core photocopying business. Intel and National Semiconductor feared that making a computer would put them in conflict with existing computer makers, which were among their top customers. HP fretted that building a cheap home computer would undercut its premium machines, which sold for around $150,000." Apple had no hesitations in using Xerox PARC's research to create its personal computer and won big.

> ***"Red oceans represent all the industries in existence today—the known market space. In red oceans, industry boundaries are defined and accepted, and the competitive rules of the game are well understood. Here, companies try to outperform their rivals in order to grab a greater share of existing demand. As the space gets more and more crowded, prospects for profits and growth are reduced. Products turn into commodities, and increasing competition turns the water bloody."***

> ***"The key is making the right strategic moves. What’s more, companies that understand what drives a good strategic move will be well placed to create multiple blue oceans over time, thereby continuing to deliver high growth and profits over a sustained period. The creation of blue oceans, in other words, is a product of strategy and as such is very much a product of managerial action."***

Companies adopting the Blue Ocean Strategy break away from the traditional competitive mindset. Instead of focusing on existing competition, companies create new markets (so called blue oceans) making the competition irrelevant.

> ***"Blue oceans denote all the industries not in existence today—the unknown market space, untainted by competition. In blue oceans, demand is created rather than fought over."***

A **common misconception is that to create a blue ocean, disruptive technology or innovation is required. **

According to the authors, blue oceans are generally created from within red oceans by expanding industry boundaries. Existing companies have the capabilities to make the shift and create a blue ocean from a red ocean - they just need to refocus their approach.

**Creating a blue ocean is less about technological innovation and more about innovative business strategy.**

The Paradox of Strategy

In the traditional competitive strategies the focus is put on outperforming rivals to gain more share of an existing market. These strategies often end up leading to bloody competition, stagnant growth, and reduced profits.

The Blue Ocean Strategy **encourages companies to break away from the traditional competitive mindset.** Instead of focusing on existing competition, companies should create uncontested market space (blue oceans), making the competition irrelevant.

Barriers to Imitation:

- Learning Barriers: Competitors will face cognitive challenges in understanding and adopting the business model and practices that make the blue ocean strategy work. The more different the new strategy is from the existing industry norms, the higher these barriers tend to be.

- Operational Barriers: Implementing a blue ocean strategy often requires **significant changes in operations and processes.** For competitors, this might mean substantial investments and a long period of trial and error.

- Brand Perception Barriers: If a **company successfully creates a blue ocean, it is often associated with the new value curve.** Competitors might find it challenging to change market perceptions that they can deliver the new value proposition as well as the pioneer.