Typewriters were first invented in the early 19th century, with the...

Kurrent is an old form of German-language handwriting based on late...

Silberstein was actually a well-known critic of Einstein’s theories...

Here's an example of a letter from Max Planck written in Latin curs...

English only began gaining traction as the dominant language of sci...

Analyzing Einstein’s handwriting

Ryan Dahn

26 August 2021

A handwritten letter featuring the famous E = mc

2

recently sold for more than a million dollars.

But what does Einstein’s handwriting tell us about the man himself?

More than 65 years after his death, Albert Ein-

stein continues to fascinate—to the extent that a

1946 letter he wrote containing the famous E =

mc

2

equation recently sold for nearly $1.25 million

at auction (see figure 1). Even Einstein’s hand-

writing has achieved pop culture status: A few

years ago, after diligently poring over hundreds of

Einstein manuscripts, typographer Harald Geisler

transformed Einstein’s cursive into a computer-

ized font.

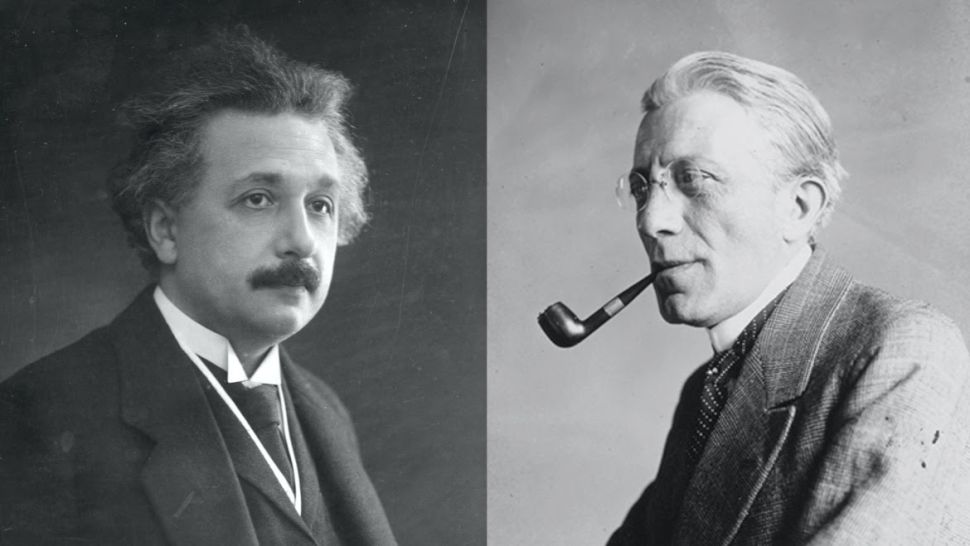

Figure 1: Dated 26 October 1946, this letter from

Albert Einstein to Polish American physicist Lud-

wik Silberstein is one of only four instances in

which Einstein is known to have handwritten the

famous E = mc

2

equation. The letter sold at auc-

tion in May for $1,243,708.

The Einstein font may seem like another piece

of Einstein-related kitsch, analogous to dorm room

posters of the famous physicist sticking out his

tongue. Yet dismissing Einstein’s handwriting as

just handwriting would be imprudent. Aside from

being worth thousands or millions of dollars at

auction, Einstein’s handwriting is a microcosm of

his turbulent life.

German cursive

Handwriting was far more important in Einstein’s

day than it is now. Typewriters were only just

becoming commonplace when Einstein came of

age around 1900. Most communication remained

handwritten, which meant that learning to write

by hand cleanly and legibly was a crucial life skill.

Einstein would have devoted much of his time

as an elementary school student learning how to

write in script. Repetitive handwriting exercises

in copybooks were the name of the game. Einstein

spent most of his early childhood in Munich, but

such an emphasis on handwriting was not partic-

ular to Germany. Where Einstein’s education dif-

fered was in the number of scripts that he learned.

Along with print writing and a cursive like the

one still sometimes taught today, Einstein would

have also learned another cursive script particular

to the German-speaking world: Kurrentschrift, or

Kurrent script, often referred to today as the “old

German script.” As shown in figure 2, the letters

of the Latin alphabet in Kurrent look quite differ-

ent from the Latin cursive that some readers may

recall learning in elementary school. The Kurrent

alphabet is famously tricky to decipher; most na-

tive German speakers today cannot read it, and

historians like myself love to complain about it.

1

Figure 2: The German alphabet in Kurrent script.

Students at German schools were taught this al-

phabet or its derivatives until 1941. At bottom

are letter combinations including ch, ck, th, sch,

and st, which are very common in German.

It is a beautifully florid, loopy script,

which—frankly speaking—also makes it highly

impractical. Many of the letters look similar. The

lowercase s and h look very different than they

do in Latin script—in Kurrent, the two letters

extend both above and below the line on which

they are written. Adding to the confusion, the

s and h also look alike. And if the handwriting

was sloppy or rushed, lowercase e, r, m, and n can

look almost identical. Because German’s system

of grammatical cases often involves distinguishing

among the articles der, den, and dem, among oth-

ers, the similarities among those letters in Kurrent

often make it hard to parse the meaning of a sen-

tence—especially for nonnative speakers. The up-

percase letters are similarly frustrating: L, B, and

C can look alike, as can J and T. (Pro tip: If you

ever come across an uppercase letter in Kurrent

that you can’t decipher, it’s probably a G.)

Why did the German-speaking world have two

different handwriting scripts? The answer goes

back to the Middle Ages. Around 1150 a new

script, blackletter (also called Gothic), emerged

from various lowercase scripts. If you’ve ever seen

a medieval manuscript, you’ve likely seen black-

letter. When the printing press was invented, in

the 1400s, the first printed books—including the

Gutenberg Bible—were set in blackletter type (see

figure 3).

Figure 3: The first lines of the book of Genesis in

the copy of the Gutenberg Bible held by the Berlin

State Library. The Gutenberg Bible was printed

in a blackletter font; the elaborate illuminations

were added by hand after the pages were printed.

Not until the Renaissance did the predeces-

sor of modern handwriting emerge. At that time,

humanists such as Petrarch (1304–74) became in-

terested in the writings of the ancient Greeks and

Romans. They combed through monasteries in

search of the earliest known manuscripts of var-

ious ancient texts. Erroneously believing that

those manuscripts, which had been written in the

early Middle Ages, reflected the typeface of an-

cient Rome, they developed a new script known

as Antiqua. By the late 1700s, derivatives of An-

tiqua had gradually replaced blackletter typefaces

in Britain and the rest of Western Europe. You’re

reading the present article in an Antiqua-based

font. (Blackletter types do survive in special cases:

Newspaper mastheads like those of the New York

Times, for example, use such fonts.)

But in the German-speaking lands and in the

Nordic countries and the Baltic states that were

heavily influenced by German culture, the use

of blackletter type—in a form known as Frak-

tur—persisted through the 19th century. Most

German-language newspapers, for example, were

printed in Fraktur until after World War II. Kur-

rent persisted as the handwritten counterpart to

2

Fraktur. Counting uppercase and lowercase let-

ters as separate alphabets, Germanophone stu-

dents had to learn how to read eight different

alphabets: the Antiqua typefaces we use today,

Latin handwritten cursive, Fraktur typefaces, and

Kurrent script.

Einstein and Kurrent

Most of Einstein’s writings were composed in

Latin cursive, including the letter auctioned off re-

cently. But his earliest correspondence was writ-

ten in the old German script; he used it almost

exclusively until he was in his mid 20s. Interest-

ingly, Einstein abandoned his use of the old Ger-

man script in the annus mirabilis year of 1905.

That May, Einstein wrote a letter in Kurrent to

his friend Conrad Habicht announcing the four

annus mirabilis papers. By July 1905 he had

switched to Latin script and would never again

use the older one. Why did Einstein switch

scripts? As far as is known, he never spoke pub-

licly about that decision, but there were likely two

reasons. The first was practical. Although all for-

eign scientists of note in that era were able to

read German—which was one of the major lan-

guages of science of the day, along with English

and French—they struggled to read letters writ-

ten in Kurrent. Even scientists who used Kurrent

with fellow German speakers, such as Max Planck

and Erwin Schr¨odinger (see figure 4), would write

to their foreign colleagues in Latin cursive (but

still in German, of course).

Figure 4: A letter from Max Planck dated 11 Jan-

uary 1942. Planck’s Kurrent handwriting, which

he used only when writing to other native German

speakers, is famed among historians for its illegi-

bility. Many scientists of Planck’s generation used

Kurrent until their death.

It was for this reason that most German scien-

tific journals were printed in Antiqua, not Fraktur,

having shifted to the former by the middle of the

19th century.

But there was probably a second reason for

Einstein’s handwriting change. Around 1900, the

German Empire was roiled by a culture war. In-

ternational avant-garde trends in art, literature,

music, and architecture coexisted in an uneasy

tension with Germany’s global imperialist ambi-

tions.

Handwriting and typefaces were drawn into

the culture war. During the 19th century, An-

tiqua typefaces and Latin cursive gradually made

inroads in educated German society. (Other coun-

tries that used Fraktur, like the Nordic countries,

largely began shifting to Antiqua in the late 19th

century as well.) The Grimm brothers, for exam-

ple, were famous advocates of Antiqua fonts. The

fonts gradually became associated with the liberal

intelligentsia and were often seen as a signal that

the writer was more international in outlook.

Predictably, that trend provoked a backlash

from conservatives, particularly among the advo-

cates of ethnonationalist theories that foreshad-

3

owed Nazism. The “Antiqua–Fraktur dispute,” as

it became known, culminated in a heated debate

in the imperial German Reichstag on 4 May 1911,

during which a proposal to begin instruction of

young children in Antiqua and Latin cursive re-

ceived 85 votes in favor to 82 against. It neverthe-

less failed because the 397-member body failed to

reach a quorum. In other words, a majority of the

German Reichstag chose to dodge the question.

(The Antiqua–Fraktur dispute was not a histori-

cal outlier; similar battles over potential reforms

to handwriting or typography were occurring dur-

ing this period in what are now Turkey, Russia,

and China.)

To be sure, there were exceptions to the gen-

eral rule that conservatives preferred Fraktur and

Kurrent and liberals preferred Antiqua and Latin

script. Before 1933, most German-language news-

papers of all political leanings were printed in

Fraktur. Thus many of Einstein’s pre-1933 pop-

ular writings were typeset in Fraktur. Older in-

dividuals who grew up with Kurrent—including

prominent intellectuals like Planck and Sigmund

Freud—often kept writing in it.

In any event, choosing a handwriting script

became an increasingly political act. Given Ein-

stein’s pacifism and his abhorrence of German mil-

itarism and nationalism, it seems highly probable

that Einstein switched to Latin cursive in 1905 for

political reasons as well as practical ones. Despite

living in Switzerland at that time, he likely wanted

to signal to foreign colleagues that he was toler-

ant, open to international communication, and not

a rabid German nationalist.

Einstein’s handwriting

After the shift, Einstein’s handwriting remained

remarkably consistent. It very much resembles the

cursive still taught in some schools today.

Some Germans in Einstein’s time who shifted

to writing in Latin script incorporated Kurrent-

style letters or flourishes into their Latin

script—most commonly a little divot above the

lowercase u, which in Kurrent was meant to dis-

tinguish it from n and m. But Einstein made a

clean break from Kurrent; his Latin script lacks

any traces of the old German script in it. He even

stopped using the eszett (β), the special German

letter denoting the combination of a “long s” (f)

and a “short s” (the lowercase s used today). (The

“long s” is not unique to German; it was used in

English until the early 19th century and is visible

on older handwritten documents such as the Dec-

laration of Independence.) Most Germans who

switched from Kurrent to the Latin script retained

the eszett in their handwriting, and it is still used

today in printed and handwritten German. The

funny extra loop on Einstein’s uppercase E isn’t

from Kurrent; it’s just one of those handwriting

quirks that make us all distinct.

What happened to Kurrent and Fraktur?

Ironically, it wasn’t the Allies’ victory in 1945 that

led to their demise but a decree by the Nazis them-

selves. Although many Nazis despised Antiqua,

Adolf Hitler did not. Fraktur and Kurrent were

too provincial for his megalomaniacal visions. If

the Germans were to be the master race, he ar-

gued, conquered peoples would need to be able

to read their language—and how could they do

so if German was printed and written in a script

that was so hard to decipher? At the height of

his power, in January 1941, Hitler issued a de-

cree to phase out Kurrent and Fraktur. Absurdly,

it claimed that the scripts had been invented by

Jews. Attempts to bring back instruction in Kur-

rent in postwar West Germany went nowhere, and

communist East Germany had no interest in res-

urrecting a script associated with conservative na-

tionalists. Today most German speakers can’t

read the script at all.

Ryan Dahn is the books editor at Physics

Today. A historian of science, he studies 19th-

and 20th-century physics in the German-speaking

lands. He is working on a biography of German

physicist Pascual Jordan tentatively titled Nazi

Entanglement.

4

Here's an example of a letter from Max Planck written in Latin cursive.

Silberstein was actually a well-known critic of Einstein’s theories.

"Your question can be answered from the $E= mc^2$ formula without any erudition"

Einstein wrote in the letter written on Princeton University letterhead.

The letter was part of Silberstein’s personal archives which were sold by his descendants.

Kurrent is an old form of German-language handwriting based on late medieval cursive writing. Its full name is Kurrentschrift, or Alte Deutsche Schrift ("old German script").

This script was widely used in German-speaking regions from the early 16th century until the mid-20th century. Characterized by sharp angles and a rightward slant, Kurrent was typically written with a quill or later with a broad-nibbed pen, leading to variations in stroke thickness.

Over time, it evolved into various styles, with one notable variant being the Sütterlin script, introduced in the early 20th century to simplify handwriting instruction in schools.

English only began gaining traction as the dominant language of science in the mid 20th century, especially after World War II:

- **After World War I** : Political tensions began to affect international collaboration. Some English- and French-speaking scientists began avoiding German publications.

- **After World War II**: The U.S. emerged as a global scientific powerhouse. As American funding, institutions, and journals became dominant, English rapidly became the global language of science.

- **By the 1970s–1980s**: English had clearly overtaken other languages in scientific publishing. Most major journals and conferences used English, even in non-English-speaking countries.

Typewriters were first invented in the early 19th century, with the earliest practical model patented by Christopher Latham Sholes in 1868. This design became the basis for the first commercially successful typewriter, produced by Remington in 1873. Typewriters gradually gained popularity throughout the late 19th century/early 20th century, especially in offices and businesses.

The Royal Typewriter Company, a prominent manufacturer only produced its 10 millionth typewriter in December 1957.